next part >

Following one globe-hopping load of Northwest potatoes reveals a lot about the world economic crisis

At the start of the french fry trail, strong Hutterite women in long dresses sliced seed potatoes and tipped their bonnets to tradition, dusting modern farm machinery with goose wings.

In April 1997, the spring breezes that blew across the Hutterite sect’s

Columbia Basin fields carried not a hint of the economic storm that would

topple Asian governments, rout stock markets and buffet the placid commune.

Hutterite farmer Albert Wollman pilots a potato planter through a Columbia Basin field. The spuds will be processed into french fries destined for fast-food outlets in Asia.

In the fields, Albert Wollman, the colony’s German teacher, started a tractor packed with more modern technology than the lunar rover. His colony farms more than 20,000 acres southeast of Moses Lake in Eastern Washington. Its 18 families cling to 400-year-old Hutterite tradition with the intensity of the Amish while harnessing the latest technology.

They need it. In the best of times, preparing a load of frozen french fries for a McDonald’s outlet in Indonesia is a formidable venture. So was following that load to its ultimate destination, which is what this tale is all about.

But the 1997 crop would face challenges unusual even in this risky business. The Hutterite fries would head into the teeth of revolution and economic turmoil that threaten the economy of the Northwest and the nation. They would be coddled by Pacific island sailors and rescued by a daring Australian engineer. The people who ate them would have no idea where they’d been.

Following 20 tons of potatoes halfway around the world is a whimsical pursuit. A french fry is an incidental item, a ketchup-drenched side dish in fast food’s global glut.

Yet fries are also a $2 billion Northwest industry, a study of mass production and global competition and an uncanny barometer of economic health. The fate of one particular load of french fries, and the lives and cultures of those who handled it, illuminates the causes and effects of Asia’s anguish the way no economic treatise ever could.

In the United States, the chief misfortunes caused by Asia’s woes are layoffs, stock market gyrations and crippling financial uncertainty.

The Northwest has lost several thousand jobs so far in key sectors—high technology, wood products and agriculture—because of falling demand for exports and depressed prices. Foreign investment, the lifeblood of the global economy, has slowed as Asian companies cancel expansions in Oregon, suspend production and put land up for sale.

In the Far East, the main tragedy—yet to sink in fully in the West—is the devastation of a substantial middle class that rose during Asia’s boom. The new middle class was important—not only for driving economies and buying U.S. products but also for boosting democracy in a region emerging from authoritarian rule.

The lowly spud provides an improbable window on these events.

Because french fries targeted Asia’s new middle class, and the growth of the middle class is an important measure of prosperity, fries are a surprisingly accurate yardstick of economic health. Their sales therefore mirror stages of Asia’s economic meltdown. The fry becomes a vehicle to understand the crisis and perhaps project its course.

Gary Finseth, who tracks fry exports as president of Portland’s Trade Stats Northwest, agrees: “French fries do appear to be kind of a lead indicator.”

* * *

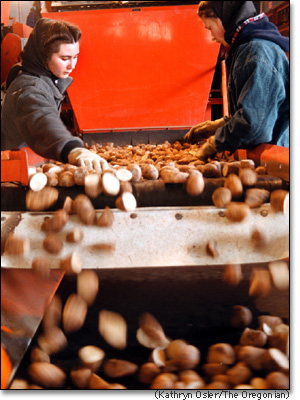

Susanna Gross, wearing a traditional Hutterite bonnet, cuts seed potatoes at the group’s colony near Warden, Wash.

The crisp, golden french fries that McDonald’s serves in red packets worldwide descend from seed potatoes grown in the high country of Central Oregon, Montana and Western Canada.

To plant the 1997 crop, Albert Wollman and other men of the Hutterite colony hauled seed stock hundreds of miles to their farm. They drove a fleet of 14 white Kenworth tractor-trailer trucks, each bearing the logo Warden Hutterian Brethren.

In their dark pants, suspenders and hats, the Hutterites resemble Amish farmers. But there’s a crucial difference: The Hutterites embrace technology.

Neutron probes measure soil moisture. Aerial infrared photographs of the colonys 3,200 acres of potato fields reveal too much fertilizer here or a clogged water jet there. Wollman’s tractor contains a computer that records harvest data on a disk. Downloaded later, the numbers reveal the effects of fertilizer, water and chemical spray on any square foot of field.

Farmers in the Columbia Basin, the vast watershed in Eastern Washington and Oregon, irrigate huge tracts to produce more russet Burbank potatoes per acre than anywhere else in the world. Even Idaho can’t come close.

Horticulturist Luther Burbank nurtured the original Burbank potato in 1872. J.R. Simplot, an Idaho potato magnate, unlocked its potential. Ray Kroc, the marketing genius behind McDonald’s, sold it to the world.

Simplot parlayed the russet Burbank’s length, high solids and low sugar content into the perfect frozen french fry. In the process he made his first fortune, helped shape contemporary America’s culture of convenience and capitalized on Asia’s economic rise.

The french fry now leads U.S. industries into new foreign markets. Sliced, or “frenched,” into thin strips, the potato produces much of the profit in fast-food chains. U.S. exports of frozen potato products almost tripled in 10 years and reached 860 million pounds in 1996, a $286 million business.

The Hutterites work long, grueling days from the moment the spring soil warms to 50 degrees and planting begins.

Potatoes bankroll the colony. Other crops, such as wheat, beans or corn, rotate through fields mainly to support the spuds.

As the 1997 planting progressed, Wollman and his brother, Ben, ran new $65,000 planters that punched eight rows of seed spuds into fluffy, sandy soil. They planted the crop in a series of 125-acre circles. From a jetliner, the rows of circles resembled giant cupcake trays baking in the searing Columbia Basin sun between Moses Lake and Hermiston.

Circle 6, a gently rolling field converted from desert in 1975, contained the potatoes that would later be tagged for Indonesia. Each circle would produce as many as 5,000 tons of potatoes, enough to make about more than 14 million large servings of fries. Each circle would be irrigated by a pipe on wheels pivoting from a post at the center.

The “circle-pivot” irrigation system, introduced in the mid-1960s, revolutionized agriculture in a region that receives 8 inches of rain a year. In one generation, with heavy government investment, dams and wells transformed the Columbia Basin from desert to food basket. Farmers who rely on the water can’t fathom city folk who want to preserve salmon at the expense of dams and irrigation.

The Warden Brethren keep expanding their farm. Mass production drives down costs to the point at which it becomes feasible to grow a potato that will be eaten in Southeast Asia, more than 6,000 miles away.

“It’s a food factory, that’s what it is,” says Chester Prior, an Oregon farmer who’s been raising circle-pivot potatoes in the Columbia Basin for 35 years. “It’s just like making a car.”

* * *

Ben Wollman repairs an eight-row potato planter in the field. The Hutterites pride themselves on self-sufficiency, repairing and often building their own agricultural equipment.

The Columbia Basin food factory’s biggest foreign customer is Japan. McDonald’s has more than 2,500 Japanese outlets.

Like the Hutterites, the Japanese capitalized on decades of hard work, close-knit communities and tight families to earn prosperity. Japan’s rigorous education system produced diligent, thrifty citizens.

The Japanese became some of the world’s best savers, producing capital for investment. Honest, well-trained civil servants guided the nation as it manufactured goods for export, achieving rapid economic growth.

Other Asian economies followed the model. South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong came next, becoming known as Asia’s four little dragons.

The more a country develops, the more fries it consumes. The dragons gobbled up fries, $65 million worth last year. Southeast Asian nations, such as Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, weren’t far behind.

The global rise of the U.S. frozen french fry—from $1.7 billion in wholesale sales in 1989 to $2.5 billion last year—was good to the Hutterites. They drove late-model pickups, air-conditioned their homes and operated expensive equipment in their commercial-sized woodworking shop.

Yet prosperity can breed temptation, in America or Japan. In 1984, the Warden Hutterian Brethren lost $2.4 million in a commodities-futures pyramid scheme.

In the 1990s, the Japanese fell victim to a pyramid scheme writ large. During the booming 1980s, they had bid prices of land and stock to astronomical heights. Japanese investors, buoyed by the high yen, bought U.S. landmarks from Rockefeller Center in New York to the Pebble Beach golf course in Carmel, Calif., alarming some Americans. Pundits urged the United States to copy Japan by picking strategic industries to promote.

Japan’s “bubble economy” burst when the overvalued stock market plunged in 1990 and land prices tumbled as much as 80 percent, leaving banks with staggering levels of bad loans.

As Japan struggled to recover, its companies poured capital into Southeast Asia in search of higher returns. U.S. investors smelled profits and followed suit.

Much of the investment during the early 1990s went into factories and other productive ventures in Southeast Asia. But high rollers went on to build lavish resorts and skyscrapers, assuming rapid growth would continue indefinitely. Banks lent money with abandon. Corruption flourished.

Japan, the master exporter, had managed to export its bubble. The stage was set for a fall that would shake not only Southeast Asia but also the entire region. And—ultimately—the world.

* * *

The Wollman brothers finished planting potatoes in May last year and moved on to beans.

For the Hutterites, each year’s potato crop is a high-stakes gamble. The colony spent more than $2,400 an acre last year on seed, water, gas, electricity and blight spray. An average acre yielded $3,500 worth of potatoes.

Multiply the difference by 3,200 acres, and net revenue exceeds $3.5 million. That’s nearly $196,000 a family.

But then subtract interest payments, equipment costs, overhead, storage, transport, taxes and potential losses on other crops rotated through the fields. Ask a Hutterite to disclose the bottom line, and like any other farmer, he’s apt to smile and talk about the weather.

Raising russets can be lucrative. Dream homes dot the Columbia Basin to prove it. But plenty of experienced farmers go broke trying, only to be bought out by big operators who perfect the formula.

“It’s a treadmill,” Albert Wollman says. “Either you speed up, or you get off. Those are the only two choices you have.”

As he operates his tractor, Wollman listens to National Public Radio. He pays particular attention to news from Asia. If all’s well with Hong Kong’s Hang Seng stock index, Wollman can enjoy classical music or Garrison Keillor’s “A Prairie Home Companion.”

But when currencies dive and banks go under, Wollman can expect Indonesians and Thais to cut back on fast food. He knows the chaos will depress demand for fries and cut the price that processors pay for his potatoes.

Once the Hutterites’ 1997 beans were planted, Wollman and the rest of the brethren turned their irrigation system to full blast.

It was while the Hutterites were checking their potatoes for blight in June that international currency traders detected cracks in the economic foundations of Thailand. It was a small place for a major crisis to begin. The rapidly developing Southeast Asian nation had an economy smaller than Oregon and Washington’s combined.

But when currency speculators noticed Thailand’s growing trade deficit, that suggested a nation living beyond its means. Quietly, they began converting their holdings of the Thai currency, the baht, to dollars.

Their sales, and their bets in futures markets that the currency would drop, depressed the value of the baht against the dollar. Bankers quickly noticed, and they sold off more baht.

Thai officials, who had pegged the baht for years at about 25 to the dollar, tried desperately to defend their currency by buying it with dollars. But the baht plunged, bottoming out at less than half its former dollar value.

Investors quickly realized that the economies of other Southeast Asian nations were precarious, too. Like Thailand, they had grown rapidly, borrowed heavily in dollars, launched grandiose business ventures and speculated wildly on property and financial schemes.

The closer investors looked, the shakier these new “miracle” economies appeared, despite years of reassuring World Bank reports. Behind the glitz of the world’s tallest buildings in Malaysia and the audacity of airplane- and auto-man-ufacturing ventures in Indonesia were rampant corruption and billions in bad bank loans.

Indonesia, run by then-President Suharto virtually as a family-owned business, was hit the hardest. Its currency, the rupiah, began a sickening slide that accelerated by autumn.

The further the rupiah fell, the more difficult it became for Indonesian companies to make payments in dollars on their outsized loans. Ultimately, the currency would lose more than 80 percent of its dollar value.

From his wheat-harvesting combine that summer, Wollman saw trouble coming. But no one—not Wollman, not World Bank economists, not Suharto himself—imagined the extent of the carnage.

next part >