An interview with

Donald Westlake

Author of the Parker novels

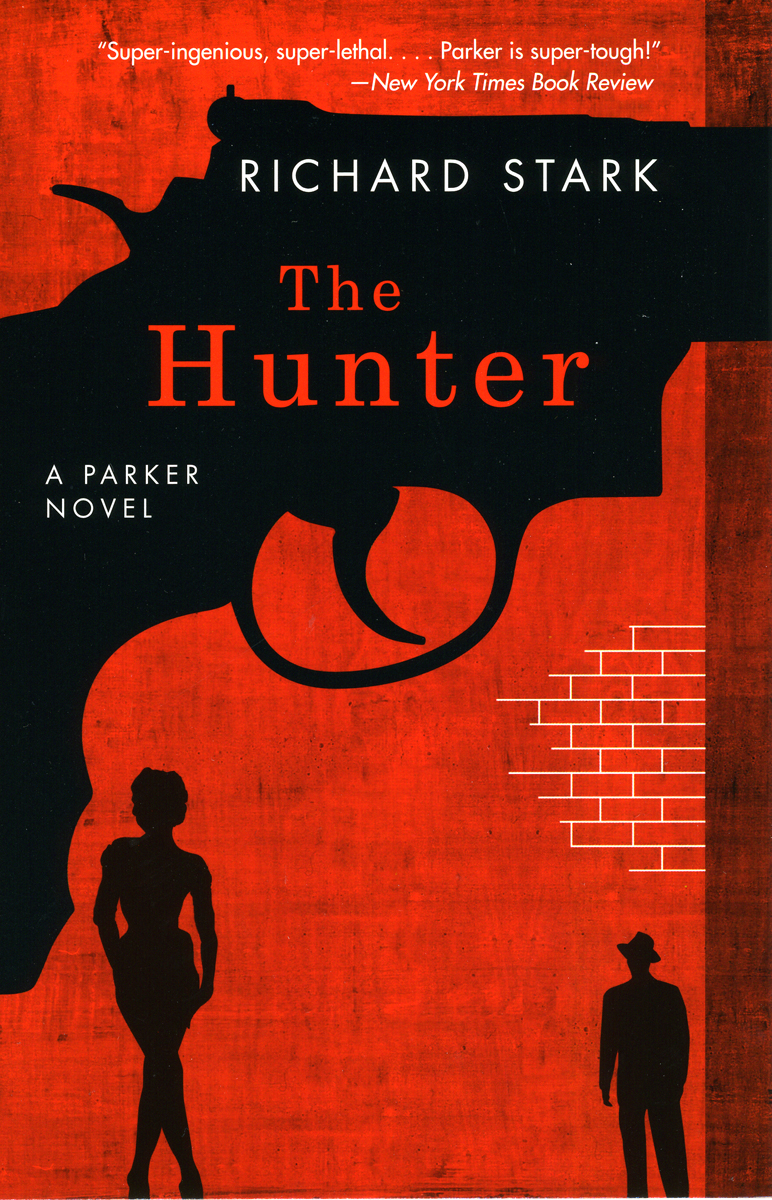

Question: Since The Hunter was first published in 1962, the Parker series has been going for over forty-five years now. Since the basic setup is largely the same—Parker gets into trouble, Parker gets out of trouble—how do you continue to come up with interesting new variations? Do the trouble itself and the way out of it come to you at the same time, or do you, like Parker, have to figure it out as you go?

Donald Westlake: I’m my own first reader. I don’t outline or plan ahead but every day tell myself some more of the story. I know the characters and I know the subject, and usually I can figure out what happens next. Sometimes the title is almost the only seed needed. Breakout came about when I realized that, in all these years, Parker had never been jailed except once before the first book. Get him arrested, and watch how he handled it. At the end of part one he’s out of jail, but not out of trouble, and at that point I came down with bad Lyme disease, in the hospital four days, unable to work for six weeks, and I kept saying, ”Well, at least he’s out of jail.“ We both hated the experience, and we both worked very hard to get him out of there. When I got back to the book, I realized the title meant the whole book so the entire thing is Parker clawing himself out of places he doesn’t want to be. They usually find their subject and their path that way, and if they don’t I simply give up writing, move to another city and use a different name.

Question: Your writing has been compared to that of Elmore Leonard, and Lawrence Block has said that he’d rather have your books on a desert island than War and Peace or Proust. Who has really influenced you most as a writer?

Westlake: I’ve always been a catholic reader, but also a bit of a sponge, taking on characteristics of what I’m reading, if I’m not careful. If I read too much Anthony Powell, my sentences gradually become longer and longer and less and less gainly. Having found my own voice (or voices) slowly and with pratfalls along the way, the last thing I want to do is imitate somebody else’s voice, particularly somebody as inimitable as Elmore Leonard. Some years ago I was hired to write a four-hour mini-series of Leonard’s Maximum Bob (like most things in the world of screens, it didn’t get made, though I got paid), and it was fascinating to burrow down into his voice and see how he did all that. There’s a continuo in his writing that’s very hard to take over to another medium.

For early influences we have to start, and almost end, with Hammett. When I first read The Thin Man there was this technique I’d never seen before and wouldn’t see again until Nabokov. A character who seems to be telling us one thing is actually telling us something quite different, even the opposite. He says he’s blithe and witty and content, but we know he’s lost and scared and very very sad. I’ve seen other writers who can do this three-dimensional thing, and I admire it tremendously.

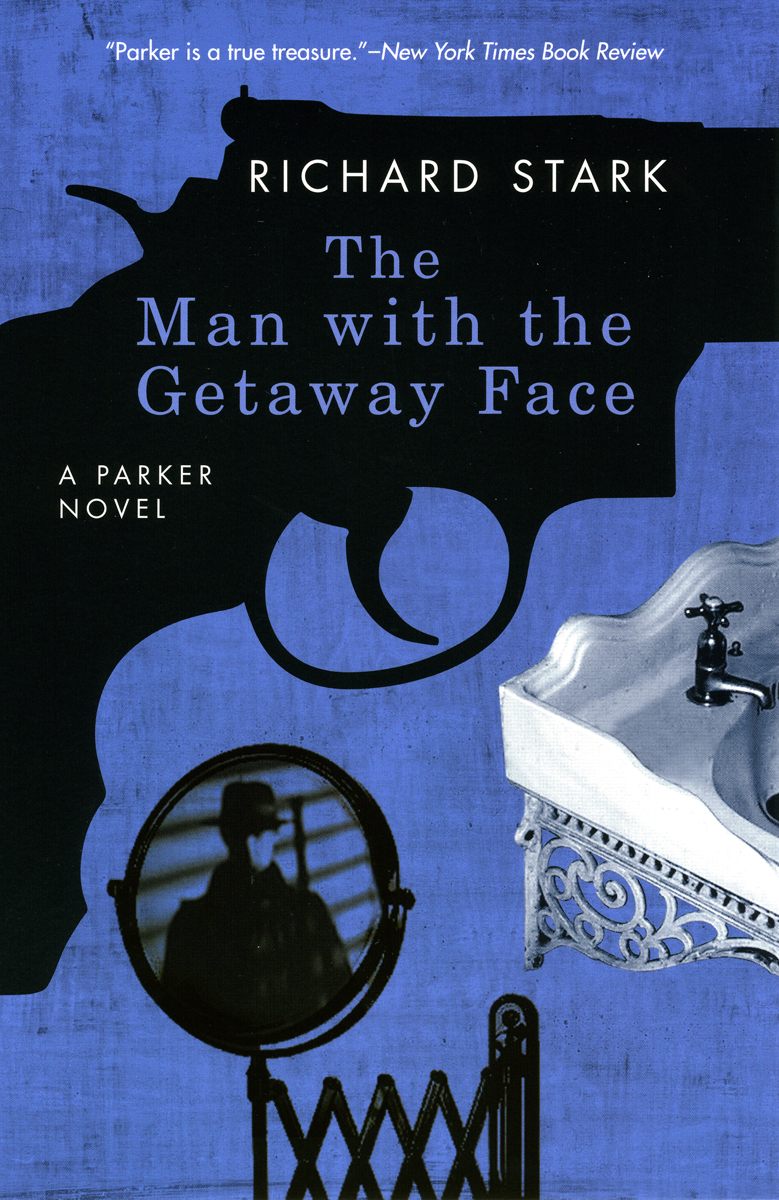

Question: You didn’t originally intend for the Parker novels to become a series. Once you realized you had a series on your hands, did you make any immediate adjustments to your ideas about Parker between The Hunter and The Man with the Getaway Face to help you be sure you could sustain the character over the long haul?

Westlake: When Bucklyn Moon of Pocket Books said he wanted to publish The Hunter, if I’d help Parker escape the law at the end so I could write more books about him, I was at first very surprised. He was the bad guy in the book.

More than that, I’d done nothing to make him easy for the reader; no smalltalk, no quirks, no pets. I told myself the only way I could do it is if I held onto what Buck seemed to like, the very fact that he was a compendium of what your lead character should not be. I must never soften him, never make him user-friendly, and I’ve tried to hold to that.

Question: Other than Richard Stark, you have also published books under the names Samuel Holt, Tucker Coe, and Curt Clark, as well as under your given name of Donald Westlake. Why all the pennames?

Westlake: When you’re first in love, you want to do it all the time. I loved writing, and I was just pushing out too much stuff for a rational marketplace to contend with. I first started putting pen names on short stories because magazines wouldn’t publish the same byline twice in the same magazine.

With the novels, Westlake had a contract to do a book a year for Random House, so if I added a second publisher I would need a second name. By the time Tucker Coe came along, both Westlake and Stark had some reputation of their own, and an emotionally-grieving disgraced ex-cop, an open wound, didn’t belong to either of them.

Some years later, I had reached that point known by a lot of writers: What if I were starting now? In this changed market, would I succeed? So I tested the waters the same way Stephen King did with his Richard Bachman novels: throw it out there under cover of darkness, and see what happens. That’s where Samuel Holt came from. (King told me once that, when his agent said they absolutely needed the pen name now because they were printing the cover, he was reading a Richard Stark and listening to Bachman-Turner Overdrive. It really is all incestuous.)

Curt Clark was sort of a one-off, because I don’t write science-fiction and here I was with this science fiction novel. Science fiction writers tend to put cute or arcane messages into their pen names, so that’s the one time I did, too. Curt, of course, means short-tempered, and Clark is a variant in spelling and pronunciation of a word one of whose meanings is writer. Short-tempered writer.

Question: Most of the characters who get hurt in these novels are tastelessly dressed, arrogant, dim, lazy or fussy; they whine about their wives, and they definitely don’t appreciate hard work. Parker may not abide by most moral codes, but whenever a character behaves like a complete jerk, his or her life expectancy goes down. Why is this?

Westlake: I hadn’t looked at it that way, but I suppose it must relate to Hemingway’s judgment on people, that the competent guy does it on his own and the incompetents lean on each other.

Question: Though Parker might deny it, I would argue that there are times when he is motivated by concerns other than business and self-preservation—even as far back as The Handle, when he goes out of his way, and risks his own life, to save the life of his associate John Grofield. And in recent novels, though he still doesn’t hesitate to kill when necessary, it seems he sometimes leaves more people alive than strict risk accounting might dictate. Do you think he’s mellowed a bit over the years? If so, would you attribute it to age, or to something else?

Westlake: I certainly hope Parker hasn’t mellowed. When one of the Kennedys was killed, a group of Hollywood actors formed an organization to swear never again to carry a gun in a film. Of course, these actors were mostly people like Don Knotts. When Lee Marvin was asked if he’d join that group, he said, ”They’re trying to put me out of business.“ I think what I’m trying to say is, Parker works within a very small umbrella. If you are under that umbrella, he will be unfailingly loyal to you. If you are outside its reach, there’s nothing to say.

Question: Parker’s work often seems unglamorous—he spends lots of time alone, driving, thinking, planning, waiting around, making phone calls, negotiating, checking numbers. He seems to value the bourgeois virtues of self-control, discipline, consistency, and focus. Do you agree Parker might make a great accountant?

Westlake: I’m not sure he has the patience for accountancy, but I’ve always believed the books are really about a workman at work, doing the work to the best of his ability. However, I see him more as working stiff than professional class.

Question: Because of the John Boorman film of The Hunter, Point Blank (1967), a lot of people imagine Parker as looking like Lee Marvin. How close is that to the man you imagine when you sit down to write?

Westlake: Usually I don’t put an actor’s face to the character, though with Parker, in the early days, I did think he probably looked something like Jack Palance. That may be partly because you knew Palance wasn’t faking it, and Parker wasn’t faking it either. Never once have I caught him winking at the reader.

Question: You’ve written over 100 books in your lifetime. Do you have any advice on productivity to share?

Westlake: I don’t know that I have any advice to share, because I pretty well don’t know how the trail led to this spot. There’s one thing I’ve learned, and that is that the writer isn’t supposed to know what he’s doing. If you know what you’re doing, you can’t do it. Later, you can look back and see, with some surprise and maybe pleasure, what it is you did. In the early days, I used to answer questions about what I meant to do next, until I realized, by the time it was in print, I’d been absolutely wrong, every single time.

![]()

Copyright notice: ©2008 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press.

Richard Stark

The Hunter

The Man with the Getaway Face

The OutfitFor information on purchasing the books—from bookstores or here online—please go to their webpages or see all our books by Richard Stark.

See also:

- Our catalog of fiction titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog