The introduction to

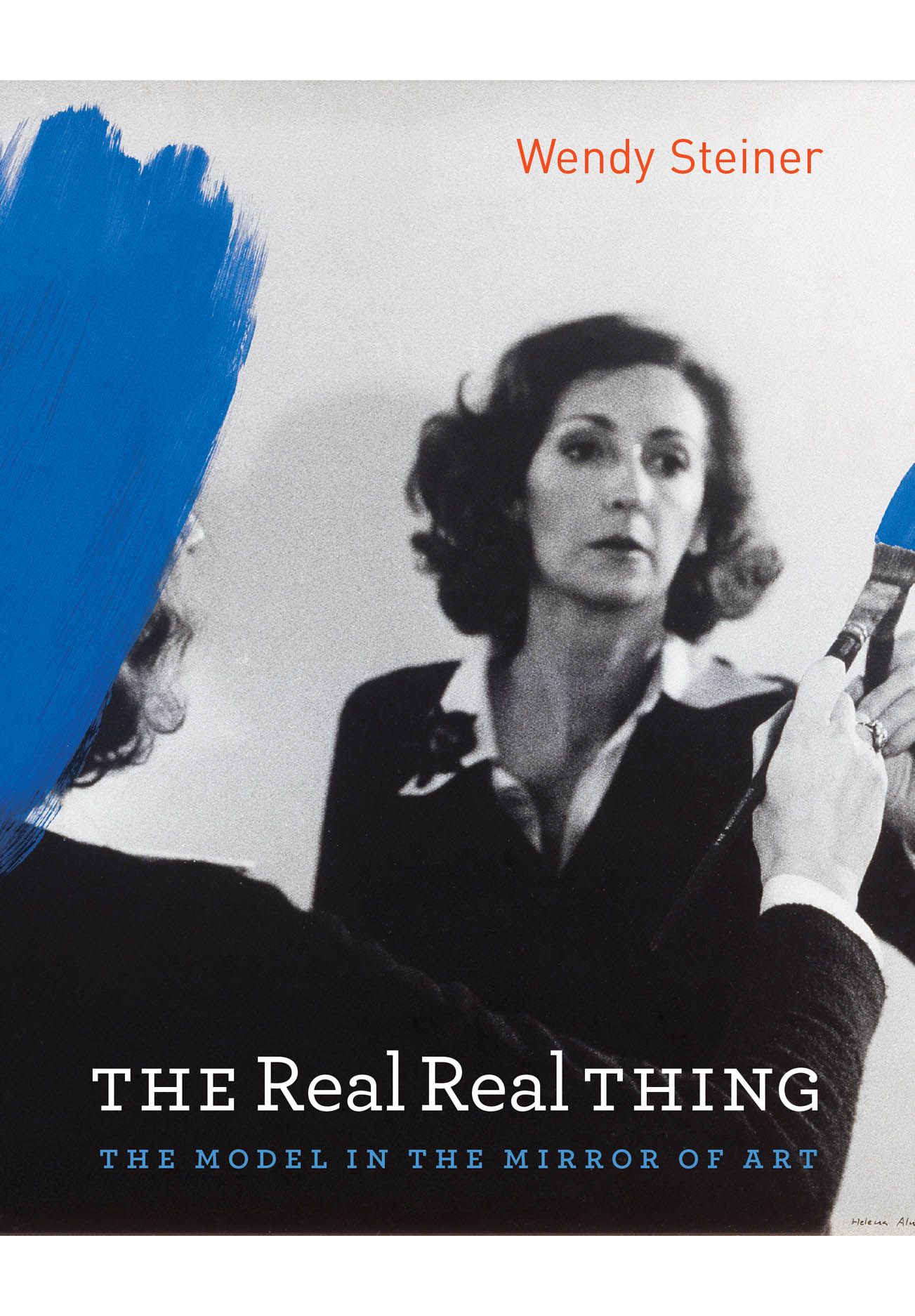

The Real Real Thing

The Model in the Mirror of Art

Wendy Steiner

Philosophy in the Life Class

One of the more unnerving aspects of the Age of Reason was its habit of placing liberationist notions in the mouths of naked ladies. The Marquis de Sade’s Justine calls her life story “one of the sublimest parables ever penned for human edification,” and Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders offers sound insights into capitalist entrepreneurship through adventures that do not read like economic philosophy. Arch and ironic as these narrators may be, their effect is not just titillation. It is as if the achievement of freedom and self-realization requires a double consciousness, as if the most authoritative voice of subjectivity is that of a thoroughly objectified woman.

Oddly, history seems to be repeating itself in our day, but this time with models inducting us into the ways of paradox. Anyone who spends much time with contemporary art will have come across this teasing figure. Marlene Dumas papers whole gallery walls with her watercolor Models, and in performance pieces Vanessa Beecroft has naked women stand about like undressed mannequins in a store window, suffering our gaze. Cindy Sherman reaches virtuosic heights as the model in her own photographs, impersonating ever-new female stereotypes. And in Life Model Goes Mad, for three weeks Tracey Emin lived naked and on view in a gallery until she picked up a brush and began to paint. In the other arts, the story is much the same. America’s Next Top Model, Girl with a Pearl Earring, Live Nude Girl, Look at Me—from reality television to films, memoirs, and novels, the arts treat the model as a symbol with much to teach us about the contemporary human condition.

Like their Enlightenment predecessors, models are professional self-objectifiers. Their job is to pose, to simulate the stillness and formal artistry of an image. They actively make themselves passive, we might say, but since they do so in the service of art rather than lust, they have better feminist credentials than Justine or Moll. Indeed, it is frequently women artists who focus on models or take on their function. Jessie Mann has pondered “What I am when I am an image” since she posed as a child for her mother, the photographer Sally Mann. Now as an adult life model and artist, she asks: “What is the mirror-self which we create on the other side of things, when we project the self . . . through art, and what of the life that spawned it does this mirror-self possess?”

Motionless on their stands, models have ample time to reflect on their still life. Such puns proliferate in the life class: the muse musing, poses as “attitudes,” the “unseemliness” of public nudity, the fine line between “lovely” and “lonely.” Being both an art object and a human subject, a model inhabits two worlds and muddles the distinction between them. “I would rise and step off the platform only to collapse embarrassingly on the deadened limbs, a marionette with the strings cut,” writes Kathleen Rooney in Live Nude Girl: My Life as an Object. But as she strikes a powerful pose, an admiring artist tells her, “You’re nobody’s puppet, Kathleen.” At once passive and active, real and virtual, the model is a twenty-first-century metaphysical conceit.

Her double nature is relevant outside the studio as well. When the narrator in Jennifer Egan’s novel Look at Me declares: “I was still the model, after all. I was modeling my life,” the implication is that nowadays we all do much the same. As Susan Sontag puts it, “To live is also to pose.” Sontag was reacting in disgust to the American soldiers posing in the Abu Ghraib photographs beside their torture victims. If the seventeenth-century empiricist Bishop George Berkeley could declare, esse est percipi, “to be is to be perceived,” Sontag sees modeling as the percipi of the media-saturated, those driven to objectify and be objectified, to experience authenticity only in the act of presenting themselves to public view. “A model’s position as a purely physical object—a media object, if you will . . . is in a sense just a more exaggerated version of everyone’s position in a visually based, media driven culture,” observes a reality writer in Egan’s Look at Me. Busy starring in our existential tableaux, we project a human condition bereft of ethics or empathy.

But paradoxically, if the model symbolizes for Sontag and others a condition of powerlessness and superficiality, those who gaze on the model are just as frequently declared the passive ones. “The people” in contemporary democracies have been reduced to viewers of their leaders’ “appearances.” According to the University of Pennsylvania political scientist Jeffrey Edward Green,

Whereas in the past, as in Athens, the spectating citizen could easily step forward and become a political actor, today most political spectators are addressed by political messages in ways that make it impossible to respond directly and extremely difficult to respond at all. The relationship between actor and spectator, in its current form, threatens the political equality prized by democracy. [The philosopher] Richard [J.] Bernstein is surely correct when he declares that the “search to find some reconciliation between the actor and the spectator continues to be one of the deepest problems of our time.”

For Sontag, this culture of the gaze is a disgrace, but for a surprising number of artists, filmmakers, and writers, it seems to be nothing of the kind. They embrace the model as a positive symbol, and their reasoning takes a different tangent from Berkeley. As Kathleen Rooney quips, “Bishop Berkeley worried that if he wasn’t looking at the world, it might disappear. I worry that if the world isn’t looking at me, I might.” This is empiricism-lite, to be sure, but it gestures toward rather profound possibilities: that the act of modeling involves an interaction with the power to ground its participants in the real. Interactions such as human love and divine caritas have been thought to do the same, and though modeling is obviously a very different matter, some artists endow it with equally rich ethical potential.

In Christopher Bram’s novel Gods and Monsters (aka Father of Frankenstein), for example, the protagonist James Whale poses for a fellow art student. “‘What I don’t like is I sit and you draw,’ he says. ‘Not fair, John. Not democratic.’” Obligingly, John undresses, too, and both men pose and draw each other. “Whale is relieved, pleased. They have corrected the balance of things, made themselves equals. One of the joys of art is that it introduces a new hierarchy into the world.” This rebalancing is short-lived in the novel, but it continues as a cherished aspiration. We might formulate it as follows: “to live is to communicate,” and its goals are the democratic values of equality and empathy. Since it is not an exaggeration to say that the introduction of new hierarchies into the world—in gender, race, and artistic experience—has been a defining imperative in the arts, the symbolic importance of modeling is hard to overestimate.

Thus, we could see Sontag and Bram as emblems of two conflicting trains of thought about the meaning of modeling. For those like Sontag, the model represents all that stands in the way of empathy and fellow feeling: a solipsistic absorption in surface and self epitomized in the makeover mantra “Change your image. Change your life!” Such a “change” is just a consumerist mystification, with image standing in for personhood and narcissism for self-realization. For those like Bram, in contrast, modeling is an interaction among parties involved in artistic creation and communication. The model and artist affect each other and come to a new understanding of themselves in this process, and viewers respond to and perhaps emulate the interaction encoded in the work.

These connections exceed the limited sphere of artistic experience. The model is ultimately “that which art represents,” a reality with an independent existence outside the work. By focusing on this figure, contemporary art can insist on its relation to the world. A real model interacts with a real artist and the resulting artwork is perceived by a real audience. Works about modeling thus can signal the reality of the creative and communicative interactions involved in the experience of art—however mediated and virtual these may at the same time be.

Such art, focusing on human interactions in the real world, inevitably enters the sphere of ethics, an area that has traditionally been distinguished from aesthetics. A realm of mirrors, of fantasy and feint, the arts have always presented a conundrum in terms of their real-world efficacy. “Poetry makes nothing happen,” declares W. H. Auden in a poem that simultaneously derides that claim. True and not true, the assertion of artistic impotence has been a valid defense against the censor, the bowdlerizer, the book-burner. Do not worry, we assure them: aesthetics and ethics are separate spheres. What “happens” in art is not happening in reality, and so it is quite safe to let anything “happen” there. The changes that take place through art are changes of mind, and democracies recognize the value of entertaining any and all such virtual revolutions.

This position we abandon at our peril, and yet the intrusion of the media into everyday experience has complicated the paradoxes of art since Auden’s day. We would hesitate, for example, before saying that television and the Internet make nothing happen, and as artists increasingly integrate the media into their work and their work into the media, it becomes harder to think of aesthetics as a sphere utterly distinct from ethics. This ethical ambiguity in art is encoded in the opposition between Sontag’s and Bram’s notions of the model. Like art, the model is a troubling ontological blur: a real person who becomes artificial in posing and gives rise to a quasi self in the form of an artistic image. On the one hand, she could represent an ethical impoverishment of the real, or on the other, new possibilities for artistic efficacy.

Seen as analogous to Sontag’s passive model—socially disengaged, morally anesthetized, depersonalized in her blank stare—art fades into the virtual woodwork, indistinguishable from the rest of media-pervaded reality. But seen through Bram’s notion, the increasing fluidity between representation and reality could make artistic interactions function as real acts of mutuality, reciprocity, and egalitarian justice. In this scenario, art makes something happen—ethical events that are not just represented in artworks, but happen in life.

Why do we need art for such interactive events? After all, that is precisely the promise held out by the Internet, with its democratic access and open source collaboration. The blogging and tweeting that went on during the 2009 riots in Iran provide a thrilling example. But such exhilarating moments have been rare; more often the Internet seems an all-absorbing counterreality rather than a means of connecting to the real and changing it. The new media have created a growing anxiety over the real: that it is increasingly inaccessible because of the intrusiveness of media in our lives; that the uncontrolled content on the Internet makes it impossible for us to tell fact from fiction or error; or perhaps that there is no difference between fact and fiction, in that reality is a construct subject to the interests of those with power and influence. These concerns are fundamentally about modeling, the relation between a reality and its representation. The sudden proliferation of nonfiction in the arts—memoirs, documentaries—is symptomatic of this anxiety toward the real, and the trail of scandals surrounding these genres—fraud, plagiarism, mis-representations of every sort—only exacerbates the situation. It is no easy task to rethink our relation to reality in light of the changes the media have wrought. The questions converging in the model are thus not only the grand aesthetic issues of our day, but the grand ontological and ethical questions as well.

In the current climate, the myth of Pygmalion is being stood on its head. Ovid tells us of a sculptor who wants to create a perfect woman, but no model is available, since all real women in his region are prostitutes. His only recourse is to imagine a perfect woman and translate this image into an artwork. No sooner has he done so than he falls hopelessly in love with his statue, Galatea, and after much ado, the gods bring her to life. Today, when it comes to animating perfection, Pygmalion has no need to appeal to the gods, given all the technologies available—plastic surgery, virtual reality, computer simulation, media interactivity, and bioengineering. Yet, suddenly Galatea seems to have lost her charms, and artists are instead yearning after the models Pygmalion so despised, the real in all its seamy vicissitude. “We cannot do without the real thing, the real real thing,” confesses J. M. Coetzee’s protagonist; “without the real we die as if of thirst.” Coetzee’s anti-Pygmalion is an illustrious author who lusts after his typist, a sometime lingerie model. But what develops between them is as moving a vision of empathy and reciprocity between flawed equals as anything in world literature. And Coetzee’s novel is by no means an isolated example of this parable.

A new myth of modeling is emerging, and in the chapters that follow, we shall enter the train of thought it entails. We shall begin soberly, dryly, with the recalcitrant question: what is a model? The attributes that emerge suit the model surprisingly well for the symbolic role she is currently playing. We have already noted some of these features. The model is a figure of ontological paradox, real and at the same time artificial. The metaphor of the mirror attends her. She is defined through the relations she enters with others in the aesthetic interaction (artist, work, audience), and that interaction reveals creation and communication to be inseparable acts. Coded in the interaction, too, are conventional hierarchies of priority, power, and value. By reversing them or rebalancing them, the model can symbolize or incite equivalent changes in other areas of experience.

Behind the current concern with models, too, is a long history of creation stories of women, and they are the subject of chapter 2. In many of these narratives there is no model. Galatea makes her appearance here, along with Pandora and Eve and other model-less female models from myth and literature. We see how Milton, Young, and Keats compensated for the absent model, and how twentieth-century modernists, on the contrary, were generally happy to keep her in exile.

Chapter 3 follows the model into the 1960s, when she suddenly reenters art as the pop celebrity. Andy Warhol and Bob Dylan invented the artist as celebrity-model, participating in an aestheticized sphere distinct from conventional reality. Several twenty-first-century films—Factory Girl, The Other Side of the Mirror, I’m Not There—are reexamining Warhol and Dylan to question the ethical stance of the artist/model/celebrity they created. Chapter 4 lays out the reasons for their concern. It shows new media putting everyone in the position of a celebrity, the model for a widely circulating public image. In the process, the reality of the model becomes problematic. “What happens to art when virtually everything is virtual?” is that art suddenly obsesses about the real, and thus the nonfictional genres of documentary and memoir have acquired an unprecedented prominence.

After this theoretical and historical background, part 2 focuses on the model as a figure in contemporary culture. Chapter 5 surveys visual works that alter traditional modeling hierarchies in order to promote reciprocity, equality, and empathy. Chapter 6 shows this goal literalized in works that actually change the world through the modeling interactions they incite. The last chapter in this sequence describes fictions that explore the aesthetics of the model by revising the traditional creation stories: Tracy Chevalier’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, Christopher Bram’s Gods and Monsters, and J. M. Coetzee’s Diary of a Bad Year.

Finally, part 3 examines current debates in art and ethics in light of this interactive aesthetics. As chapter 8 reveals, it would be a mistake to believe that all contemporary art about modeling promotes liberal values or posits a paradoxical state of culture. Recent debates between classicists and modernists, for example, turn on the use of the past as a model. The chapter takes issue with both approaches—the frozen formulas of classical beauty epitomized in Frederick Hart’s sculpture, as well as the “whirl of infinite innovation” espoused by apologists of the avant-garde. The alternative offered is the interactive engagement with the past in works by John Kindness and Peter Eisenman.

Chapter 9, the coda of this argument, suggests how all-pervasive the issues surrounding interactive aesthetics have become, by considering phenomena as diverse as debates in bioethics and the musical Hairspray. Hawthorne’s “The Birth Mark” is a connecting link, a creation story about the difference between formal perfection and interactive beauty. Its lesson is as relevant to the President’s Council on Bioethics as to the dancing liberators of Hairspray’s racist, sexist, “lookist” Baltimore.

The Real Real Thing can be seen as the third study in a loose trilogy that began with The Scandal of Pleasure (1995). That book defended the arts against censorship and literalist interpretation on the grounds of its virtuality, its difference from reality. The next, Venus in Exile (2001), argued that beauty was again becoming a central value in the arts, but re-understood this time in interactive terms. The Real Real Thing elaborates this interactive aesthetics. Those versed in semiotics will recognize my pervasive debt in all three to Roman Jakobson, Jan Mukařovský, and others.

It might appear that The Real Real Thing’s concern with the efficacy of art contradicts the central premise of The Scandal of Pleasure: that art signifies a virtual world, separate from the real. But though this trilogy does circle back on itself, its tail does not consume its head. Nonfiction, documentaries, reality TV, interactive art, and all the rewriting of modeling myths conceivable could not eradicate the virtuality of art. What these indicate instead is the enormous effort under way in culture to process the changing relation between the real and the virtual wrought by contemporary media, technology, and science.

It is only two decades since the culture wars that provoked Scandal, and yet the challenges the arts address today seem entirely different. The problem now is not that art will be treated as a threat to the body politic, but that the body politic has become hard to distinguish from art. Not just artists, but all of us are concerned with the issues the model raises: power differentials in the process of communication, the permeation of the media into everyday existence, and the value of art in the buzzing circuit board we call reality. If, as in the eighteenth century, these paradoxes find voice in a female figure of unorthodox philosophical pedigree, it is hard to imagine one who could better convey the hopes and ironies of the current situation.

![]()

Copyright notice: The introduction to The Real Real Thing: The Model in the Mirror of Art by Wendy Steiner, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2010 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Wendy Steiner

The Real Real Thing: The Model in the Mirror of Art

©2010, 232 pages, 50 halftones

Cloth $32.50 ISBN: 9780226772196

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for The Real Real Thing.

See also:

- Our catalog of art, photography, and design titles

- Our catalog of literary studies titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog