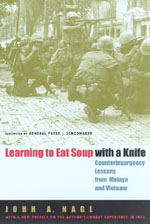

The preface to

Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife

Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam

John A. Nagl

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Spilling Soup on Myself

Authors generally learn something about their subject matter, and then write about it. I took the opposite approach. Eight years after beginning my research into counterinsurgency and a year almost to the day after the publication of the first edition of this book, I deployed to Iraq to practice counterinsurgency as the Operations Officer of the First Battalion of the 34th Armored Regiment, the “Centurions.” From September 24, 2003, through September 10, 2004, I was privileged to serve as Centurion 3 in Khalidiyah, a town of some 30,000 between Fallujah and Ramadi in the Sunni Triangle.

The experience was searing. The Task Force was built around a tank battalion that had been designed, organized, trained, and equipped for conventional combat operations. The enemy we confronted was implacable, ruthless, and all too often invisible. Our yearlong confrontation in Al Anbar Province was bloody and difficult for the insurgents, for our soldiers, and for the population of the region. It was without a doubt the most intense learning period of my life.

The experience of fighting insurgents in Iraq made me think again about the views expressed in this book—assessments of the British army in Malaya and, especially, of the American army in Vietnam. Rereading my work now, I am surprised by how much I was able to understand of counterinsurgency before practicing it myself and simultaneously appalled at some of my presumptions and errors. In the few pages of this preface I hope to point out omissions and missteps from that first edition, written before my own physical immersion in counterinsurgency, while highlighting some of the things I feel I got right the first time. It is my sincere hope that the book may be of use to those attempting to make our armed forces more effective in what promises to be a long struggle against enemies who fight freedom with the ancient art of insurgency.

Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife

T. E. Lawrence’s aphorism that “Making war upon insurgents is messy and slow, like eating soup with a knife” is difficult to fully appreciate until you have done it. Intellectually grasping the concept that fighting insurgents is messy and slow is a different thing from knowing how to defeat them; knowing how to win, in turn, is a different thing from implementing the measures required to do it.

This is perhaps the most basic flaw in the book that follows. There is something of a blithe sense that defeating the Communist insurgents in Malaya was easy once Sir Gerald Templer and Harold Briggs showed the British army what to do, and that the American army could similarly have won in Vietnam if only it had adopted earlier the changes promulgated by Creighton Abrams and Bob Komer. The truth is rather more complex. Changing an army is an extraordinarily challenging undertaking. Britain was able to adapt to defeat the insurgency in Malaya for many reasons, but those reasons certainly included the British army’s comparatively small size and its organizational culture that had been honed in a number of small wars fought over generations. Changing the American army is a task of an entirely different scale, a challenge that the organization struggled with during the Vietnam War.

The army’s adaptations in Vietnam were ultimately too little too late to defeat the insurgency there. By contrast, the army has adapted much more rapidly to the challenge of insurgency in Iraq. My own personal experience is illustrative of the larger challenge and response. Task Force 1-34 Armor was preparing for high-intensity combined arms warfare in July of 2003 when it was notified that it would deploy to Iraq; by September, two of its three tank companies were conducting combat operations in the Sunni Triangle mounted on Humvees and dismounting to fight as dragoons, with just one company fighting from M1A1s. In the intervening sixty days, the battalion had been issued new weapons systems and vehicles ranging from machine guns to up-armored Humvees. It reorganized its combat vehicle crews and maintenance teams, designed and implemented counterinsurgency training, and deployed halfway around the world to fight a kind of war that, if not new, was new to the soldiers of Task Force 1-34 Armor.

Difficult as these transformations were, the combat soldiers of the Task Force in some ways had an easier time adapting than the staff. The essence of the line soldiers’ mission remained closing with and destroying the enemy. Their additional tasks of supporting the local government and winning the trust of the local people were subordinate to and in some ways a natural outgrowth of their ability to provide security. The battalion staff had to change its entire approach to combat, shifting its focus from battle-tracking enemy tank platoons and infantry squads who fought in plain sight to identifying and locating an insurgent enemy who hid in plain sight. This much more difficult change demanded an entirely different way of thinking about combat—a different level of professional knowledge about a different kind of war. The enemy we faced could only be defeated if we knew both his name and his address—and, often, the addresses of his extended family as well. Understanding tribal loyalties, political motivations, and family relationships was essential to defeating the enemy we faced, a task more akin to breaking up a Mafia crime ring than dismantling a conventional enemy battalion or brigade. “Link diagrams” depicting who talked with whom became a daily chore for a small intelligence staff more used to analyzing the ranges of enemy artillery systems.

The book that follows pays ritual obeisance to the importance of intelligence in counterinsurgency operations, and to the canard that “To defeat an insurgency you have to know who the insurgents are—and to find that out, you have to win and keep the support of the people.” All true, truer than I knew at the time I wrote it. But the task of winning and keeping the support of the population is far more complex than I had understood. In the following pages, I note that the British did a better job of gaining the trust of the Malay population, but I don’t properly emphasize that when the insurgency began they had been in the country for well over a century, developing long-term relationships and cultural awareness that bore fruit in actionable intelligence.

The United States is working diligently in Iraq, as it did in Vietnam, to improve the lives of the people. Dollars are bullets in this fight; the Commander’s Emergency Response Program (CERP), which provides field commanders funds to perform essential projects, wins hearts and minds twice over—once by repairing infrastructure, and again by employing local citizens who are otherwise ready recruits for the insurgents. CERP is helping with the painstaking process of building relationships with the Iraqi people, resulting in some intelligence from those we help—but not enough, not yet.

One of the most frustrating aspects of the war on the ground in Iraq is responding to the scene of an attack, whether on U.S. or Iraqi security forces, with the sure knowledge that at least some of the bystanders have critical information on those responsible, but being unable to obtain that information from them. The people know the insurgents; they are often tied to them through blood or marriage or long association. The combination of these bonds and the likelihood that they will be killed in the night if they are seen talking to security forces in the day all too often intimidates those who genuinely want peace in Iraq, but see no way to achieve it at a bearable personal cost. Winning the Iraqi people’s willingness to turn in their terrorist neighbors will mark the tipping point in defeating the insurgency. Those who contend that “American forces have lost the support of the Iraqi population and probably cannot regain it” are incorrect; in fact, the majority of the Iraqi population prefers the American vision of a democratic and free Iraq to the Salafist version of Iraq as Islamic theocracy. The key challenge is empowering the intimidated majority to enable Iraqi and American security forces to eliminate the criminal insurgents.

The Irreplaceable Role of Local Forces

When I wrote this book, I underestimated the challenge of adapting an army for the purposes of defeating an insurgency while simultaneously maintaining the army’s ability to fight a conventional war. I also understated the importance of local forces in defeating an insurgency and the difficulty of raising, training, and equipping them. Creating reliable, dedicated local forces during the course of an insurgency that targets not just the local soldiers and police but also their families truly is a task as difficult as “eating soup with a knife.”

Local forces have inherent advantages over outsiders in a counterinsurgency campaign. They can gain intelligence through the public support that naturally adheres to a nation’s own armed forces. They don’t need to allocate translators to combat patrols. They understand the tribal loyalties and family relationships that play such an important role in the politics and economies of many developing nations. They have an innate understanding of local patterns of behavior that is simply unattainable by foreigners. All these advantages make local forces enormously effective counterinsurgents. It is perhaps only a slight exaggeration to suggest that, on their own, foreign forces cannot defeat an insurgency; the best they can hope for is to create the conditions that will enable local forces to win it for them.

In their turn, however, foreign forces have much to offer local forces battling an insurgency. Western armies bring communications packages, training advantages, artillery and close air support, medical evacuation, and Quick Reaction Forces that together contribute dramatically to the confidence, morale, and effectiveness of the local forces, especially when trainers are embedded with the locals.

The fact that the insurgents often attack local forces suggests that they realize how essential those forces are. Task Force 1-34 Armor worked diligently to mentor the local police force and two battalions of the Iraqi National Guard during its year in Khalidiyah. Recruiting, organizing, training, equipping, and employing these forces often appeared to be an uphill fight, as the Iraqi leadership both wanted and resented American leadership and logistical and financial support. Building trust through joint operations and shared risks ultimately resulted in some intelligence sharing, but the task of creating reliable forces that could independently guarantee local security was incomplete when the Task Force passed responsibility for these units to its follow-on force, the Currahees of Task Force 1-506 Infantry. The effort to raise, train, and equip these forces is likely to take much time and energy, but it could not be more important. The British forces in Malaya had earlier and better success with this process than did the Americans in Vietnam, with the possible exception of the Marines’ Combined Action Platoon program in I Corps. Some of the lessons of the British and Marine experiences may be of use today as the United States increasingly turns its attention to the task of creating Iraqi security forces that can defend Iraq against both internal and external threats. Their success is the key to unlocking victory in Iraq—victory for, and by, the Iraqis.

Innovation under Fire

This book suggests that tactical leaders in the field can spur innovation that, when accepted by higher commanders, dramatically reshapes an army in combat. The experience of the U.S. Army in Iraq certainly supports that contention. Tank battalions, which just weeks previously had been required to execute missions no more politically complicated than “Attack” and “Defend,” learned while in combat how to conduct Area Denial operations and Special Forces–style raids even as their battalion leadership conducted political negotiations with local leaders and trained and equipped Iraqi police and National Guard forces. Task Force 1-34 Armor learned to integrate Civil Affairs, Psychological Operations, and Counterintelligence Teams into its daily counterinsurgency operations. Linking up in theater and inventing doctrine on the run, these Counterinsurgency Teams were essential to the success of the battalion in winning the hearts and minds of the good guys—and of uncovering, capturing, and killing the bad ones.

The United States Army has taken remarkable strides to adapt to the demands of counterinsurgency in Iraq in a process it calls the “Modular Army.” Stepping away from the 15,000-soldier division as the center of gravity of the army, this program creates more nimble 4000-soldier Units of Action able to operate independently over a wide area. The army is also taking steps to increase the numbers of soldiers with much-needed special skills including the counterintelligence and civil affairs soldiers that Task Force 1-34 Armor put to such good use in Khalidiyah. Programs to recruit additional Arabic speakers are underway in both the Active Army and in the National Guard, adding another essential weapon to the counterinsurgency capability of the nation. Much more remains to be done as the army creates a force capable of the cultural and linguistic sophistication necessary to defeat a very capable enemy.

Winning the Long War: The Integration of National Power

The army is adapting to the demands of counterinsurgency in Iraq at many levels, from the tactical and operational through the training base in the United States. However, Iraq is but one front in a broader war against Salafist extremists dedicated to eliminating Western influence from the Islamic world; winning the struggle may take decades. There is a growing realization that the most likely conflicts of the next fifty years will be irregular warfare in an “Arc of Instability” that encompasses much of the greater Middle East and parts of Africa and Central and South Asia. To cope more effectively with the messy reality that in the twenty-first century many of our enemies will be insurgents, America’s armed forces must continue to change.

The 2005 Quadrennial Defense Review specifically evaluates the ability of the Department of Defense to prevail in irregular warfare. However, the fight to create a secure, democratic Iraq that does not provide a safe haven for terror is not primarily a military task. Counterinsurgency requires the integration of all elements of national power—diplomacy, information operations, intelligence, financial, and military—to achieve the predominantly political objectives of establishing a stable national government that can secure itself against internal and external threats. Britain was able to employ all of these elements of power remarkably well in Malaya; the process of integration took the United States longer in Vietnam.

Final victory in today’s fight depends upon the integration of the nations in the Arc of Instability into the globalized world’s economic and political system. The army is working hard to adapt to the challenge of the global insurgency. The other departments of the federal government, and governments throughout the entire world, are steeling themselves for a protracted struggle. They also must adapt themselves to prevail in this fight, creating an operational capability to influence the actions of other nations and of subnational groups in the Arc of Instability.

Much of the burden of that struggle will continue to be borne by the young men and women of the American armed services and by their local force comrades in arms. It was truly an honor and an inspiration to serve in Iraq with some of the finest soldiers our country has ever produced. Their spirit of selfless service and determination to fight so that others can live in freedom should humble all of us. It is to them that I dedicate this edition.

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages xi-xvi of Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam by John A. Nagl, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2005 by John A. Nagl. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

John A. Nagl

Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam

With a new Preface. Foreword by General Peter J. Schoomaker.

©2002, 2005, 280 pages

Paper $17.00 ISBN: 0-226-56770-2For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife.

See also:

- A catalog of books in history

- A catalog of books in war and remembrance

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects