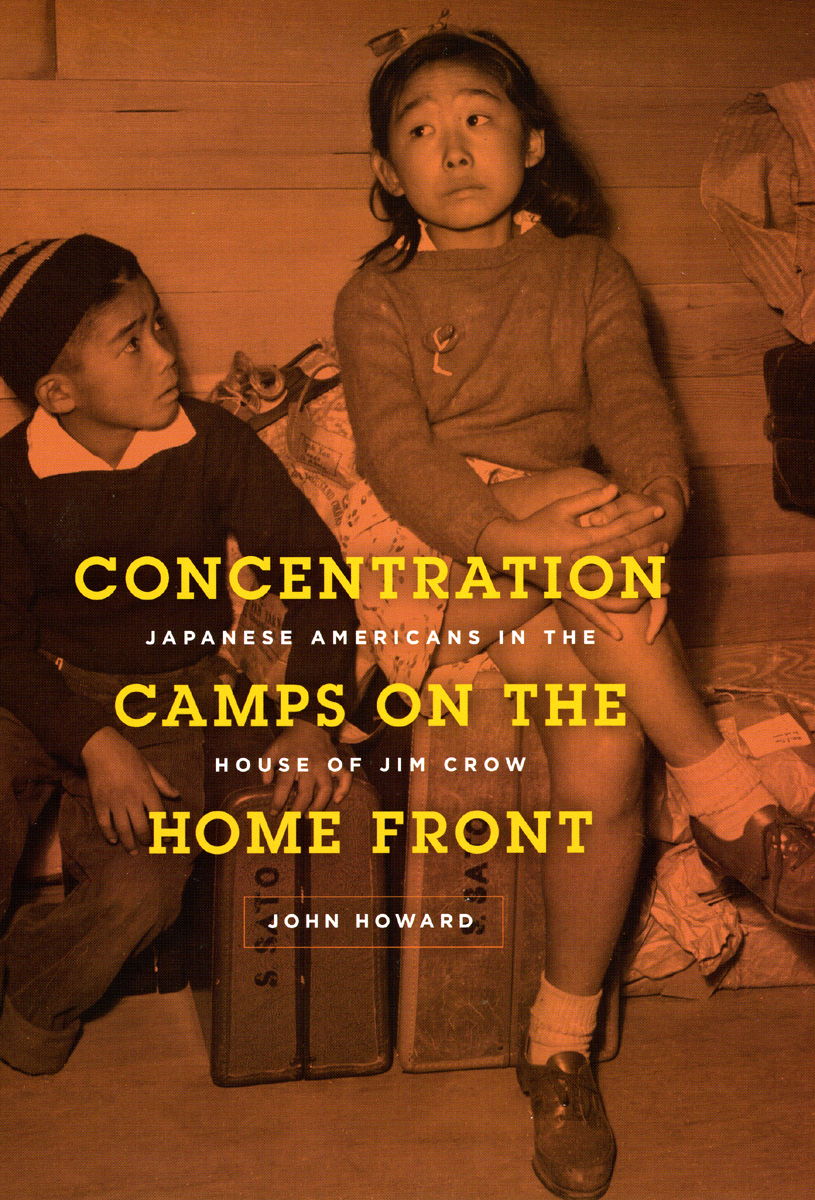

An excerpt from

Concentration Camps on the Home Front

Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow

John Howard

Introduction

Neither a military hero nor sports figure, neither an elected official nor popular entertainer, Earl Finch cultivated a unique celebrity in mid-twentieth-century America. Raised poor in rural Mississippi, Finch was known only to his family and a small circle of peers as of 1943. By 1945 he would meet with President Truman; he would be spotlighted in press accounts and magazine features; and he would go on to be warmly remembered in innumerable memoirs of the war years. His friends and acquaintances would span the globe. Neither a Carnegie nor a Rockefeller, Earl Finch was a philanthropist of limited means, a do-gooder with what seemed a single cause.

Prone to immoderate gift-giving, Finch embodied the most prominent symbols of openhandedness. He was Santa Claus, turning up at Christmastime and doling out presents to youngsters. He was the Easter bunny, securing thousands of decorated eggs for hunts in the spring. He was the Christian servant, a disciplined Southern Baptist who followed Jesus’ parable on eternal life: he fed the hungry; he visited the sick; he went to those in prison; he welcomed the strangers. The strangers to the Deep South during World War II, those most in need, as Earl Finch saw it, were Americans of Japanese descent. Finch’s altruism was focused on the victims of U.S. concentration camps, the 120,000 Japanese American citizens and longtime residents forced from their homes on the West Coast and indiscriminately incarcerated in the interior, particularly those locked up in the two camps in nearby Arkansas. And he was especially concerned with the second-generation (or Nisei) men who, despite all this, had volunteered to serve in the war effort, those soldiers training in the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, just down the road from Finch’s hometown.

According to the legend, corroborated by veteran Keiso Nakagawa and others, Finch first met one or two of the “lonely” soldier boys—names are rarely mentioned—on the streets of Hattiesburg, gazing “forlornly” into a store window. He extended an invitation to dinner. Alerted to their plight, Finch went to work wholeheartedly on behalf of Japanese Americans. When told about the children of Jerome and Rohwer, Arkansas, he sent toys and candy by the truckload. When informed of the dietary dilemmas resulting from displacement, he arranged shipments of rice, soy, and tofu. When he heard about racial segregation at the local USOs—the United Service Organizations clubs for the off-duty entertainment of troops—he helped form a new Aloha Center, and he contributed furnishings to USO clubrooms within the Arkansas concentration camps. Finch threw dinners and parties; he organized rodeos and road trips for the servicemen. After they left for combat in the European theater, he kept up correspondence. After they returned home—some on stretchers, some in coffins—he made hospital calls and paid visits to the next of kin.

There was ceaseless speculation about Earl Finch. To some, the lanky white Mississippian seemed too good to be true. Behind the selfless humanitarianism surely lurked self-serving impulses, perhaps even sinister machinations. For one thing, Finch had an uncanny ability to procure those delicacies that, in World War II America, were in shortest supply. Might he be connected to the underworld? Or, worse still, the enemy? At the least, Finch’s style raised alarm. In practicing his piety, he didn’t always manage the quiet humility required by the Gospels. In its glowing feature on Earl Finch, the Saturday Evening Post—that profit-minded purveyor of white American wholesomeness—spoke these worries, but only through the skeptical voice of a jaded New Yorker. The “smooth, fast-talking” owner of “the lavish Broadway night club” frequented by Finch and company bluntly posed the question no one else seemed willing to enunciate: “What’s his angle, anyway?” Taking the query as a framing device for his article, writer Maurice Zolotow examined Finch’s murky motivations, which many found “perplexing in the extreme.” Zolotow reached the happiest of conclusions: “Spontaneously, and with all the fullness of his heart, [Finch] became a friend of an unjustly persecuted and cruelly misunderstood minority. . . . Finch [wa]s that rare being, a man without an angle.” Zolotow believed Finch, who succinctly stated his reasons for helping the 442nd, including the recently incorporated 100th Infantry Battalion from Hawaii: “I do it because I like these boys.”

Well, I believe Finch too. Indeed, I’ve discovered that Finch took a special liking to a series of young men of Japanese descent. I want to take Earl Finch at his word; or more to the point, I want to explore how his words—“I like these boys”—could be variously interpreted, both then and now. I don’t want to suggest that, armed with a heat-sensitive twentieth-first-century night vision, a technologically superior post-Stonewall gaydar, we can now clearly see in retrospect the homoeroticism that mainstream midcentury media refused to acknowledge. Quite the contrary, I propose that queer implications in Finch’s activities were right on the surface, fully perceptible at the time. More interesting, in my view, are the ways in which those implications were negotiated by Earl Finch and his many Japanese American friends. More interesting still—or, rather, more available to historical inquiry—are the ways in which queer implications were largely tamed and contained in media representations. Like the dangerous parallels repeatedly evoked between the moral culpabilities of American racism and European fascism, any comparisons between Earl Finch’s peculiarities and a subversive nonconformity required vigilant if subtle denunciation. In a period of intense international conflict, fraught with countless ethical ambiguities, Finch’s eccentric homespun generosity was normalized and valorized; it was made to comport with a mythical American goodness born of the rural heartland. . . .

Un-natural but not Unamerican

Born in 1915 on a farm outside the village of Ovett, Mississippi, Earl Finch was only twenty-seven years old when he first became acquainted with Nisei in Hattiesburg. Thus, of the thousands of Japanese Americans who trained at Camp Shelby, he was scarcely older than most and was younger than many. At six feet two inches tall, however, he stood above almost all. And in the symbolically rich world of masculine privilege, size mattered. Already effeminized in midcentury popular film, as Gina Marchetti has shown, Nisei men short of stature guarded against further aspersions. For example, when stock-depleted quartermasters sent them outerwear and underwear appropriately sized but originally intended for the Women’s Army Corps, the men of the 442nd chose the WAC garments with care: “The raincoats were handed out, but not the panties. We didn’t want our men to be known as being æmahu’ (gay).”

Earl Finch stood tall, and he stood out. Photographs of dinners show the fair-complected Finch seated at the center or the patriarchal head of the table, wearing a suit and tie, surrounded by unnamed Nisei in uniform. In a largely biracial South, where interracial friendships rarely survived childhood and where, in adulthood, they were countenanced only in hierarchical work environments, Finch might have been called anything but a companion to Japanese Americans. Rather, with extraordinary frequency and consistency, the prematurely bald Finch was referred to—and subsequently has been remembered—as “the godfather of the 442nd.”

But why not comrade? As would be asked of any able-bodied twenty-seven-year-old male in 1943, why wasn’t Finch also enlisted in the armed services? As the Saturday Evening Post was quick to point out, whereas Finch’s brother Brownie had signed up for the U.S. Navy, Earl “was turned down as 4-F”—unsuitable for military service. More precisely, Finch volunteered for the prestigious Officer Candidate School in late October 1942, but his application was denied. He requested regular induction in early 1944 but was rejected due to flat feet and a heart ailment. Thus, as a white civilian seemingly advanced beyond his years, Finch took on the popular wartime mantle of booster, “a sort of guardian,” particularly as board member for the USO. If his references to his charges, to “my boys,” mirrored the racist infantilizing of black southern men, they also resonated with the prevalent if ambivalent American depictions of soldier boys, sailor boys, and flyboys sent overseas to kill. The pseudo-intergenerational relationship between Finch and the press’s representative Nisei soldier was further manufactured through the latter’s reference to Earl as “Mistuh Finch,” as white writers rendered the ostensibly accented English. After a fatal injury in Italy, for example, one Japanese American “boy”—again, unnamed—reportedly offered these last dying words: “Just say good-by to Mr. Finch for me.” A year older and, in some sense, a man of greater professional distinction, Protestant minister and 442nd chaplain George Aki insists, “I always called him Mr. Finch.”

White military leaders and concentration camp officials helped cast Earl Finch as a “mentor” to the 442nd by relying on a common narrative of American success ideology. Finch’s personal history, they suggested, was an admirable and imitable tale of class ascendancy. Failing to finish high school, Finch nonetheless had brushed the dirt off his work boots and, with gumption and industry, had become proprietor of any number of local enterprises: a bowling alley, a furniture store, a clothing shop, and—important in the iconography of southern aristocracy—a farming operation or ranch. In truth, Finch was solidly middle class, seldom generating balances of more than $2,000 in his personal or commercial bank accounts. Locals gossiped about the way he seemed to spend well beyond his earnings. In fact, he often simply brokered deals for his Japanese American friends, particularly those from the territory of Hawaii who had been spared incarceration and thus had not lost their assets in distress sales, as had most from the mainland. Moreover, the 442nd took pride as a regiment of successful gamblers: their newsletter masthead spelled out 442 with three correspondingly arranged dice, and as their regimental slogan, they chose the crapshooter’s phrase “Go for broke.” These were men with money to spend. But in the South, Finch had entrée where Japanese Americans were subject to racial discrimination. It was Finch’s whiteness as much as his business acumen that facilitated his ironic title—second only to godfather—of “benefactor” of the 442nd.

Earl Finch’s involvements with the 442nd were not merely financial but also social, perhaps sexual. If the Saturday Evening Post was loath to explore this, J. Edgar Hoover’s Federal Bureau of Investigation was eager. The former readily explained away Finch’s lack of interest in young women: he lived with and cared for his disabled mother, confined as she was to a wheelchair. The latter viewed Finch’s bachelor status, the fact that he had never married, as a worrying sign of something deeper. The FBI inquiry was solicited by an intelligence officer at Camp Fannin, Texas, after Finch visited Japanese American soldiers there and promised to “pay for all the ice cream [they] wanted.” Agents intercepted Finch’s voluminous incoming mail; they interrogated Hattiesburg residents and confidential informants. As suspected, many locals “considered Finch to be peculiar in that he never associates with girls.” According to one former schoolmate, Finch “always exhibited more or less of an abnormal attitude toward the opposite sex [and was] unnatural in this respect.” As another pointed out, Finch had once used his clout to help purchase “a home so a Japanese officer could live in it.” The FBI interpreted these actions and character traits as inherent in Finch’s “extreme egotism,” a narcissism shot through contemporaneous psychiatric accounts of homosexuality, the physical self desiring its mirror image. Whereas the Saturday Evening Post sympathetically portrayed Finch as a humble loner, “not much of a joiner,” the FBI by contrast viewed him as a “mentally unstable” headline-grabber. In sum, “his association with the Japanese [American] soldiers who in turn pay him a great deal of attention and cause him to be publicized apparently satisfies his personal desires.”

And yet in closing its investigation, the FBI had to concede that Finch generally enjoyed a “good reputation.” To a person, neighbors and acquaintances absolved him of any wrongdoing. Speaking a common refrain, a reporter for the local paper told the FBI agent that he had “known Finch personally for many years and [wa]s positive that [he had] no un-American motive.” The banker likewise “had known [the] subject for many years and . . . [the] subject’s family,” and he had “never observed any un-American tendencies.” Even as the armed forces attempted to cleanse its homosocial ranks by purging its homosexual comrades, as Allan Bérubé has demonstrated, even as Second World War and soon Cold War rhetoric would entangle homosexuality with espionage and sedition, Earl Finch emerged in popular representations as a heroic American with peculiar habits. Indeed, as I’ve shown elsewhere, rural queers successfully negotiated an environment of quiet accommodation not so much because they were invisible or undercover; but rather—to repeat the words of Finch’s neighbors—because they were known. Embedded in local communities, bound by relations of kinship and familiarity, sexual nonconformists often were known as queer but not as subversive. Because their queerness was known or assumed, it could thereby safely be disregarded.

In broader fields of cultural production, in mainstream representations aimed at national audiences, rurality vindicated sexual nonconformity. Critical to Earl Finch’s acceptance was the focus on his more authentically rural and thus masculine experiences. “Finch never traveled more than 100 miles,” the Evening Post told its readers, “until he became involved in the Nisei problem.” The magazine accentuated not those high times in the big cities—New Orleans, Chicago, New York. Rather, along with the Hattiesburg American, it emphasized the regular Sunday gatherings at Finch’s Rolfin Stock Farm, the 542-acre compound replete with chickens, mustangs, sheep, and free-ranging cattle, photographed while being branded. Writers mentioned Finch’s grandfather, who first farmed the soil, but rarely his father—who, as a janitor at the Hattiesburg Public Library, was an archetypal victim of agricultural decline, the mass economic exodus from field to town. Finch liked to hunt and ride, as evidenced by pictures astride his horse, oddly reminiscent of heroic military statuary; his more lucrative but gender-suspect profession as haberdasher received scant attention, even though shared by Harry Truman. Similarly, of Finch’s Japanese American guests—three hundred attended one rodeo—journalists noticed not the many urban Californians in the 442nd, known for their relative sophistication, the occasional zoot suit, and flair for dance. Instead, they harped on the barefoot Hawaiians of the 100th Battalion—the plainspoken farm folk who, as in racist depictions of African Americans, exhibited culinary preferences for watermelon, lemonade, and fried chicken. Although these imagined island field hands seemed a bit rough around the edges, their crude masculinity would reach appropriate refinement, not defilement, under the tutelage of so-called patron saint and country gentleman, Earl Marvin Finch.

Utilizing dialect and depicting comic scenarios, white reporters often infantilized Japanese American men. They homogenized the men of the 442nd, whose words rarely were attributed to them by name in print. Such racial grouping further served to deflect the possibility of sexual relations between Earl Finch and any one (or more) of them. That is, a racist understanding of Asian Americans as a homogenous mass—as all looking alike, especially in uniform, and thus uniformly heterosexual—helped defuse the prospect of individual non-normative desires. And yet we might speculate that some queer readers of the day would recognize Finch as the definitive “rice queen”—a white man whose same-sex desires were structured by depersonalizing, dehumanizing racial fetish, an exclusive attraction to men of Asian descent. Without the testimony of Earl Finch, however, and without complete sexual candor from the Japanese American men who joined the U.S. Army, we should not rush to conclusions about the egalitarianism of their intimate relationships.

During and particularly after the war, Japanese American men documented their experiences in their own words. In memoirs, Daniel Inouye and many others described their military service as proof of their loyalty, as evidence of their worth as Americans. They wrote very fondly of Earl Finch, as if implicitly sharing a quest to shed outsider status—in his case sexual, in their case racial—by becoming the consummate insider, the superpatriot. Or, by supporting the ultimate insider, Uncle Sam. Perhaps to some Japanese Americans, Earl Finch evoked Uncle Sam: paternalistic, nationalistic, well-intentioned, and asexual. According to veteran Chester Tanaka, who apparently thought of the nation in terms of the “opposite” gender, Earl Finch was “the man who symbolized America at her finest.”

Many Nisei writers rhetorically overlooked Finch’s queerness, even as it seemed to draw him closer after the war. As superpatriot Mike Masaoka explained, Nisei from Hawaii felt obliged to repay Finch’s hospitality, and so they invited him to visit them on the islands. One or two ever so subtly expanded the invitation: “You come to Hawaii.” Finch came all right. And stayed. He relocated to Hawaii in 1949 and lived there until his death in 1965. Though he never married, in the 1950s he “adopted” two sons around the age of twenty from Japan—first Seiji Naya and, later, Hideo Sakamoto. As Sakamoto explained his arrival in Honolulu: “In the beginning, I was thinking that this was my guardian, my sponsor. He paid for my school. But a couple of weeks later, Seiji told me I had to act like a son. The next day, I called him æDaddy.’ That’s the way he needed it, I found out. It was a real close bond.”

Related forms of humanitarian international adoption, transferring children from poorer to wealthier countries, from poorer to wealthier parents and guardians, have been criticized as a malign by-product of Western imperial expansion, which generates, exacerbates, and benefits from such inequities. However, adoption within Japan historically has been accepted as a means—not unlike arranged marriages—for shifting the social and economic responsibility for a young person from one house, household, or family registry to another. Boys in particular have been passed into apprenticeship roles designed to enhance future prospects. Thus, adoptions for what was perceived to be better schooling and training overseas became viable options before and after the war.

Meanwhile back in postwar Mississippi, Finch’s friend Herbert Sasaki married white local Arnice Dyer and took up residence in Hattiesburg, around the corner from Finch’s mother and father. Sasaki sang Finch’s praises, though he harbored doubts about his departure: “It was kind of bad, you know, leaving his parents.” Afterward Sasaki would take Earl’s folks out for drives in the country, since “they liked it so much.” I asked Herbert Sasaki the question posed by so many over the years, “What motivated Earl Finch?” He responded either with incomprehension or, much more likely, discretion: “It’s very hard to say.”

If early twenty-first-century theories privilege the metropolis as the key site of queer sexualities, similarly many mid-twentieth-century representations cast the city as the logical home for sexual difference. For rural Americans negotiating their own sexual and gender nonconforming desires, behaviors, and identities, such biases of understanding could be manipulated to circumvent oppressive forces and carve out enabling social and physical spaces. In his dealings with locals and in his interviews with the press, Earl Finch seemed particularly adept at such negotiation. When Daniel Inouye, Mike Masaoka, Keiso Nakagawa, Herb Sasaki, Chester Tanaka, and hundreds of other Nisei soldiers joined in the all-male rodeos, road trips, and rural recreations organized by Finch, they assented to and participated in official and mainstream media discourses that largely normalized the activities. By emphasizing those second-generation Japanese Americans from the agricultural regions of Hawaii over those from the Little Tokyos of California, by highlighting Finch’s career as a rancher as opposed to a merchant, and—crucially—by crafting their interactions not as egalitarian interracial friendship but as hierarchical humanitarian mentorship, the highly publicized 442nd Regimental Combat Team would not be implicated in criminalized queer acts with the unmarried, un-enlisted southerner known to the FBI as “unnatural.” Capitalizing upon the productive vagaries of queer innuendo, euphemism, and double entendre, Finch likewise did not demonstrate an underlying gay self but rather circulated narratives open to varied interpretations. Thus, when asked “What’s your angle?” Finch could cagily proliferate a multitude of meanings, then as now, by responding, “I like these boys.”

Like Earl Finch, the wartime concentration camps for Japanese Americans seemed unnatural to many, the living arrangements inhumane and unjust, as will become all too apparent. But as this book further attempts to demonstrate, the camps yielded mixed results, including—against all intuition—an affirmation and empowerment of many Japanese Americans, based upon a human inclination to work together, to share burdens and benefits, to cooperate. Certainly, the camps were not un-American. United States history is filled with compelling analogies, if brought to light for comparison. Following in an impressive historiography of Japanese American incarceration, described below, Concentration Camps on the Home Front attempts to illuminate some of the unflattering precedents for incarceration, as well as noble models for overcoming it. With the help of theorists and interpreters of human difference, the book endeavors to take us beyond American contexts to see if one or two broader hypotheses can be hazarded about the nature of human conflict and resolution.

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 1–10 of Concentration Camps on the Home Front: Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow by John Howard, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2008 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

John Howard

Concentration Camps on the Home Front: Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow

©2008, 356 pages, 20 halftones

Cloth $29.00 ISBN: 9780226354767

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Concentration Camps on the Home Front.

See also:

- Our catalog of history titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog