An excerpt from

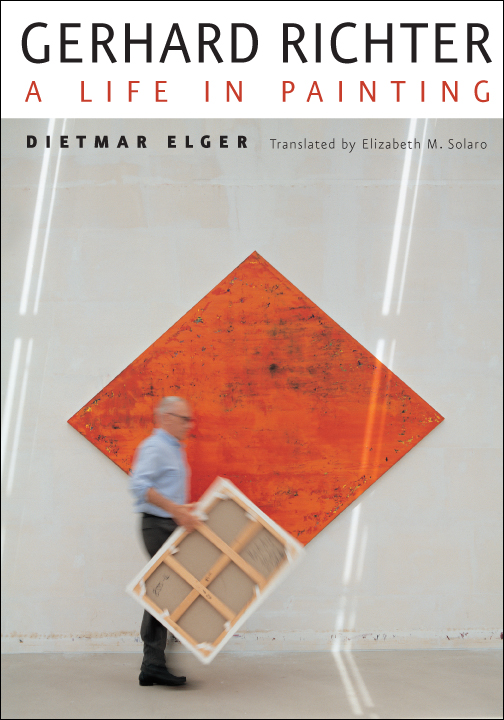

Gerhard Richter

A Life in Painting

Dietmar Elger

Dresden

The city of Dresden is one of Germany’s oldest urban centers. Located near the country’s eastern border, it was, before World War II, a charming baroque city and an important government seat, internationally renowned as a place of great culture and learning. It was in Dresden that the great Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich had plied his trade in the early nineteenth century, and by 1900 the city had become a bustling hub of contemporary art.

Dresden is also the birthplace of Gerhard Richter, one of Germany’s most important postwar painters and, indeed, one of the most esteemed artists in the world today. Richter was born on February 9, 1932, in the Hospital Dresden-Neustadt, not far from the city center. Of course 1932 is important in German history for other reasons as well. Within months of Richter’s birth, Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers’ Party gained a majority in the Reichstag, or national parliament, and on the eve of the boy’s first birthday, Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. Taking advantage of a fire set in the parliament building, possibly by his own people, Hitler then hastened to consolidate his power and to launch the radical military regime that came to be known as the Third Reich. There is no need to dwell here upon the countless atrocities committed by Hitler and the Nazi military, which very nearly extinguished whole cultures and their communities. Suffice it to say that Dresden was a singular tragedy. By the end of the war, it would lie in rubble, irremediably transformed, first by Hitler and his drastic policies, and then by Allied bombing, which left vast sections of the city in cinders and many thousands of its inhabitants dead.

Richter was still only a boy when the war ended in Europe. Yet the artist recalls growing up an ordinary child in an ordinary household struggling to cope with the extraordinary pressures of National Socialism. His childhood, he says, was largely pleasant if uneventful—though he is quick to admit that his memories are shaped by the self-absorbed perspective of youth and may not always reflect the facts.

Gerhard’s mother, Hildegard Richter, neé Schönfelder, was twenty-five years old when the future artist, her first child, was born. Hildegard came from a solidly middle-class family who were the proprietors of a large brewery in the Bavarian city of Kulmbach, but throughout her life, first as a daughter and then as a wife, she never quite attained the elevated lifestyle she desired. Her father, Ernst Alfred Schönfelder, had been a talented concert pianist who unfortunately demonstrated little talent for brewing. Within a few years of giving up his vocation to take the helm of the family enterprise, he had propelled it into bankruptcy. Herr Schönfelder then moved his family to Dresden with the idea that they could live on their investments while he pursued a new career in music. This project never amounted to anything more than a hobby, but still, the Schönfelders were in Dresden, which suited Hildegard. She adored the bustling city and growing up there together with her younger sister, Marianne, and older brothers, Alfred and Rudolf.

In Dresden Hildegard trained as a bookseller, a highly esteemed profession in Germany. She had a passion for literature and music and, like her father, played the piano well. “My mother had such an elitist way about her,” Gerhard said decades later. “To be a meaningful person, from her perspective, one had to be a writer or artist or intellectual.” However, she never displayed any particular affinity for the visual arts.

Gerhard’s father, Horst Richter, had studied mathematics and physics at the Technische Hochschule in Dresden and taught at a gymnasium, the equivalent of an American high school. Horst and Hildegard married in 1931, but it was not a happy match: the couple’s interests and values were entirely different. Hildegard enjoyed a brisk social life, was a voracious reader, and had many cultural interests, while Horst seems to have been more of a homebody and less driven to succeed than his wife was. Dogged by chronic unemployment in the late 1930s, as Germany’s social, economic, industrial, and educational systems were transformed under National Socialism and as the country ramped up for war, Horst finally landed a teaching position in Reichenau, a town today called Bogatynia and located in Poland, about eighty kilometers south of Dresden. When the Richters moved there, Reichenau had a population of about 7,400 and supported a variety of industries, including cement manufacturing, coal mining, and textiles. The most attractive thing Richter recalls about Reichenau was that it had a public swimming pool. Gisela, Gerhard’s younger sister, was born there in November 1936.

The move from the lovely, bustling metropolis of Dresden, with its theaters, concerts, and cinemas, to Reichenau, a drab locale steeped in heavy industry, was a blow to Hildegard—although it likely saved her life and those of her children. The small town offered little stimulation, and to make matters worse, she regarded her husband as her intellectual inferior. Horst was a deeply religious man who sustained himself by attending Protestant Evangelical services every week. Hildegard countered his piety with her own fierce beliefs, absorbed from the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche.

Because Horst was a teacher, he was forced to join the National Socialist Party, though, as Gerhard remembers it, his father never bought into the party’s ideology. In fact Richter does not recollect that anyone in either of his parents’ families was an avid supporter of Nazism; like so many other German families at the time, the Richters and the Schönfelders were apolitical. In the countryside, in little towns like Reichenau and the even smaller town of Waltersdorf, where his parents later moved, they were spared the necessity of attending party rallies or participating in special deployments. Later, in 1942, with the war in full force, Gerhard was conscripted into the Pimpfen, the program that prepared children to become members of the Hitler Youth. Still, he managed to avoid most of the odious paramilitary field exercises and tent camps thanks to his mother, who willingly filled out and signed his absence forms, claiming illness.

Gerhard, who went by the nickname Gerd, was his mother’s favorite, and Hildegard projected the full sum of her unfulfilled hopes and ideals onto her son. She encouraged his early interest in Nietzsche and in Goethe, Schiller, and other classic writers, whose books she kept about the house. She had nothing but reproach for Horst, given his failure to distinguish himself, going so far as to intimate to young Gerd that Horst may not even have been his father.

On September 1, 1939, when Gerd was seven, Hitler’s troops invaded Poland, marking the start of World War II. Almost immediately, Horst Richter was drafted into the military and mobilized to the eastern front. He served in Hitler’s military for the duration of the European campaign, with the result that he was absent during the most crucial years of his son’s development. The war was hard on the Richters, as on other families, in ways that belie a little boy’s cheerful memories; it touched them in ways Gerhard would begin to comprehend only much later, as an adult. His mother’s brother Rudi was killed early in the war. Her sister, Marianne, was first sterilized and then starved to death by the Nazis in the Psychatrische Landesanstalt Großschweidnitz, a hospital for the mentally disabled. Richter would commemorate the two in paintings from 1965: Uncle Rudi and Aunt Marianne.

In 1943 Hildegard moved her children out of Reichenau to the even smaller town of Waltersdorf (population 2,500), in the extreme southeast corner of Germany, on the border with the current Czech Republic, about twelve kilometers from Zittau. There the family lived on the village’s eastern edge, in subsidized housing, which Richter would later recall as “depressing.” The austerity of the Richters’ financial situation made it necessary for Hildegard to sell her beloved piano.

As fighting raged on, Horst Richter was shifted to the western front where he was captured by the Allies. He spent the rest of the war in an American prisoner of war camp. Finally released in 1946, he made his way home to an indifferent wife and to children who greeted him as a stranger. As with many returning veterans, Horst’s presence served only to disrupt the harmony of the family. Through a series of moves and good fortune, Gerhard and his sister had been spared any direct experience of the horrors of war. In fact, thirteen-year-old Gerd found the end of the campaign to be a great adventure, replete with genuine rifles and pistols. He and his friends discovered discarded weapons everywhere and held target practice in the woods surrounding Waltersdorf. “I always found that interesting—when things go bang,” he later told Jürgen Hohmeyer of the Hamburg-based newsmagazine Der Spiegel. Even today, with unusual candor, Richter stands by his youthful enthusiasm: “That was the most exciting time of my life, and I think of it fondly.”

For a long time after the war, groceries were hard to come by. Waltersdorf, located in eastern Germany, had come under the control of the Soviets as a result of the Potsdam Agreement, drafted by the USSR, the United States, and the United Kingdom to regulate the postwar occupation and reconstruction of Germany and other territories. Gerd and his father would take to the road, sometimes for days, trying to sell various household objects or trade them for food. As a former Nazi Party member, Horst would never again be allowed to teach. Desperate for employment, he finally went to work as a laborer in a textile mill in Zittau.

Gerd had already begun to commute to Zittau to attend a college-preparatory school. But, alas, he failed nearly every subject; he even brought home poor grades in drawing. After a year he was forced to drop out and instead enrolled in a vocational school, also in Zittau, that offered courses in stenography, bookkeeping, and Russian. Two years later, in 1948, he graduated.

The months and years immediately following the war were, on the one hand, chaotic and difficult but, on the other, characterized by an atmosphere of political awakening, possibility, and intellectual freedom—at least for a while. The provisional government, the Sowjetisches Besatzungs-Regime, donated many books expropriated by the Soviets from private collections to public libraries, which put long-forbidden literature again within reach. In the local library in Waltersdorf, Gerhard devoured books by authors who had been persecuted by the Nazis: Thomas Mann, Lion Feuchtwanger, Stefan Zweig. Their writings awoke in him a nascent literary ambition, and the teenager tried his hand at romantic verse. At the same time, an endless supply of illustrated books prompted his own first drawings. Richter vividly remembers a nude figure copied from a book in 1946 as his earliest serious effort. And he recalls his parents’ reaction when they found the drawing under his bed. For once, Horst and Hildegard agreed on something: both were shocked at the work’s erotic content—but also enormously proud of their son’s obvious talent.

When Gerhard heard one day that Hans Lillig, an artist from the region, had come to Waltersdorf to paint a mural at the elementary school, he rushed over to see. It was his first encounter with a professional artist, and he was allowed to watch Lillig work. He marveled at the painter’s technique and the progress of the mural, a fascination that may have lingered and perhaps even affected his decision later in art school to specialize in the genre. Meeting Lillig also afforded the budding artist the chance to show some of his own drawings to a “colleague” for critique.

By 1947 things were starting to come together for Gerhard: by day he attended vocational school in Zittau, and at night he took a painting class. Before the end of the course he realized, with a certain satisfaction, that no one at the school had the skill to teach him anything more. He began to concentrate intently on art, experimenting with various media, painting watercolors, and collecting old master prints published by E. A. Seemann Verlag in Leipzig. In one self-portrait from 1949, Richter painted himself brimming with confidence. The gleaming right eye fixes the viewer, as if to proclaim the young artist’s talent, while the left side of the face and the shoulder recede into darkness. “It had to do with being an introvert. I was alone a great deal and drew a lot”. He remembers having grown increasingly private after his family moved to Waltersdorf. “Automatically I was an outsider. I couldn’t speak the dialect and so on. I was at a club, watching the others dance, and I was jealous and bitter and annoyed. So in the watercolor all this anger is included. … It was the same with the poems I was writing—very romantic, but bitter and nihilistic, like Nietzsche and Hermann Hesse.”

By the time Gerhard finished vocational school in 1948, he had moved out of his parents’ house in Waltersdorf and was living in a residence for apprentices in Zittau. Though deeply preoccupied with art and art history, he was also a pragmatist and thus decided to pursue a more sensible vocation. He considered various options, including becoming a forest ranger; the inspiration was short-lived, however, as the program involved a course of intense physical training and, according to Richter, he simply was not strong enough to qualify. Lacking a gymnasium diploma meant professions such as medicine and dentistry were also out of the question, so his mother tried to arrange a place for him in a printing plant. This he rejected after the first interview, repulsed by the strong smell of chemicals.

With his talent for drawing, young Gerhard finally secured a position with a sign painter in Zittau. He spent about six months cleaning and priming old stencils of shop signs, preparing them for repainting by other employees. Bored, he quit the job in February 1950 and hired on as an assistant set painter at the municipal theater in Zittau, where he painted the sets for productions of Goethe’s Faust and Wilhelm Tell. This was much more to his liking. “I enjoyed the work, which had at least something to do with art when we painted the large backdrops.” When the season ended, however, the employees were, as was customary, assigned less glamorous jobs such as tending to the building’s upkeep. Told to repaint the stairway, Gerhard refused. By then, five months into the job, the apprentice saw himself as a full-fledged artist and above such things. He was abruptly fired.

Somewhat later Richter would claim that he had also apprenticed with a photographer—a bit of misinformation that still occasionally makes it way into his biography. He did actually receive a simple plate camera from his mother as a Christmas present in 1945, and the father of his friend Kurt Jungmichel operated a photography lab in Waltersdorf, where Gerd was allowed to develop film and work on his own pictures. The 1965 painting Cow II is based on one of his earliest photographs. As this and other of Richter’s gray photo-paintings began to attract attention in the mid-1960s, critics and collectors frequently asked if the images were personally significant. Some in fact were, but Richter for many years would deny it, or dismiss any personal association as irrelevant. Not only did he want to protect his private life—Richter has always been a deeply private person—but by then he wanted the public to engage with the issues of media and reality that had come to preoccupy him in his practice.

But that would all come much later. In 1950, after two aborted apprenticeships, Gerhard was just deciding to become a professional artist, and not everyone was as impressed with his talent as he was. When he applied for admission to the Dresden Art Academy (Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden) for the winter semester of 1950–1951, his portfolio was summarily rejected. His work was deemed too bourgeois for his country’s socialist sensibilities, but he received a valuable suggestion: if he really wanted to train at the academy, he was told, he should first get a job at a state-run business and then reapply. State employees apparently received preferential treatment when it came to competitive admissions. So Richter went to work as a painter at the Dewag textile plant on October 2, 1950. The following spring he again applied to the Dresden Art Academy and this time was promptly accepted. He quit the textile plant on May 31, 1951, and packed his belongings. After sixteen years he was on his way back to Dresden, his hometown, to pursue a career in art.

In 1951 Dresden was still in ruins. Only a few buildings had been rebuilt since the devastating Allied air attacks of February 13 to 15, 1945. It was almost as if the great cultural metropolis had vanished in a single, incendiary stroke. “Everything had been destroyed,” Richter recalled. “There were only piles of rubble to the left and right of what had been streets. Every day we walked from the academy to the cafeteria through rubble, about two kilometers there and back.” The students’ path led them past the ruins of the Frauenkirche (the Lutheran Church of Our Lady), the most important landmark of the former baroque capital.

Because Richter’s parents did not belong to the “class of workers and peasants” but to the academic middle class (even though his father worked as a manual laborer), he did not qualify for a full scholarship. Most students at the academy received decent stipends, but he had to make do with a third as much. At first, he lived with a great aunt on his mother’s side in Langenbrück, some distance from the city. Aunt Gretl, as he called her, also gave him money to purchase art supplies and other necessities.

Days at the academy began punctually at eight o’clock, with eight full hours of instruction. In addition to studio courses, such as painting and life drawing, the school offered a strong academic curriculum, with subjects ranging from art history and aesthetics to Russian, Marxist theory, and political economy. Richter learned an enormous amount at the academy: the techniques of working in various media, the precise observation required in life drawing, and lessons of composition, all of which, even then, he regarded with some skepticism. It was important to the instructors that their charges acquire skills in a broad spectrum of traditional painting genres—portrait, still life, landscape. “It was a very sound education,” Richter acknowledges. “Perhaps these experiences stir up a certain Ur-trust in Art, which has always kept me from wanting to be a ‘modern’ artist.”

Richter valued the cultural openness of this postwar period, especially in the field of literature, but it turned out to be only a brief interlude. Soon after the founding of the German Democratic Republic on October 7, 1949, the state called its artists to duty. Walter Ulbricht, the first secretary of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, propagated the idea of the so-called “new man,” the “hero of work” who would help build a strong, socialist Germany. Art was obligated to support and, indeed, to celebrate this labor: “In that the artist visualizes what is new and progressive in humanity, he helps in training millions to this new humanity.” Art was subordinated to political doctrine, instrumentalized as a medium for educating citizens, and there was little doubt about the government’s preferred style—socialist realism—which was only to be deployed on prototypical subjects imported from the USSR. The job of the artist in the GDR, known in the West as East Germany, was to create monumental statues of Marx and Lenin and to represent the worker in the factory and the farmer in the field as heroes in the battle for a triumphant socialism.

In the academy’s library, the books available to students covered the history of Western art only through impressionism. Publications about modern and contemporary trends in art—which under the Soviet regime, not unlike that of the Nazis, had come to be viewed as a symptom of late bourgeois decadence—were stored in closed stacks, and students were allowed to look at them only in exceptional circumstances. Even work associated with Die Brücke, the group of expressionist artists founded in Dresden in 1905 by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, was deemed inappropriate for young, susceptible eyes and minds. Instead, the nineteenth-century Russian realist Ilya Repin, the German Adolf Menzel, and the twentieth-century social realist Berhard Kretzschmar were lauded as exemplars. “It was all politically and ideologically grounded,” in Richter’s assessment. “The goal was socialist realism, and the Dresden academy was especially obedient in this regard.”

Because art was meant to perform a social—that is, public—function, the private market was suppressed. The state, its institutions, and its factories became the only customers for art and thus could discipline artists who would not conform simply by withholding commissions. What resulted was inevitably homogeneous, art grounded in the lowest common denominator. “Socialist realism is truly idiotic. It doesn’t bring anything, is hokus, nothing but illustration,” said Richter in 1985, annoyed, even after forty years, that the practice persisted in East Germany. “And the people don’t get anything out of it. There is nothing alive or new in that art.”

There were two notable efforts to liberalize the strict stylistic guidelines of socialist realism during Richter’s time at the academy, if only to a small degree. On June 17, 1953, workers marched in protest of the ongoing militarization of their country, as well as the absurdly high production quotas being mandated by the Soviets. The protests in Berlin and elsewhere were quickly suppressed, but they brought into sharp relief the dreadful economic plight of East Germany at the time. Exacerbating the situation was a growing crackdown on “illegal” organizations and political groups. Surviving in East Germany, both physically and creatively, was becoming harder and harder, and great numbers of workers were leaving the country.

In the aftermath of the June uprising, East Germany’s Deutsche Akademie der Künste (German Academy of the Arts) requested that the government’s strictures be loosened to encourage greater artistic diversity—but to no avail. The following year, however, saw a small gain when the magazine Bildende Kunst published several works by Italian realists Renato Guttuso and Gabriele Mucchi, who rendered social themes in styles influenced by Picasso, Van Gogh, and other artists of the European avant-garde. But Guttuso and Mucchi had both fought against fascism during World War II, as partisans, and Guttuso had been a member of the Italian Communist Party since 1940. Given their impeccable credentials, the Italians were tolerated, and in 1955 Guttoso was even designated an affiliate of the German Academy of the Arts in East Berlin. Pablo Picasso was also accepted in East Germany because he was a member of the French Communist Party, which he had joined in 1944, following the liberation of Paris. As one of the party’s most illustrious members, he took part in the 1949 Congrès Mondial de la Paix in Paris and designed the event’s now-famous poster, featuring a white dove.

Richter took full advantage of this tiny rupture in government policy to follow, at a safe remove from the academy, the debates about the new stylistic and intellectual challenges of modern art. The students “had a general sense of what was going on,” he says. “The stuff from the West circulated. Everyone had something to pass around that excited us.” The budding artist also had an aunt in the West who sent him books, catalogs, and, now and then, the photography magazine Magnum. Like many of his fellow students, Richter produced, alongside the official assignments, a second, private body of work, painted in the evenings and on weekends at home. “I certainly painted more than the other students,” he says. “There were of course my assignments—the realistic still lifes, nudes, landscapes, etc., etc.—and, at the same time, I attempted more interesting experiments in modern art.”

A second, even more important step toward artistic independence was Richter’s decision to enroll in the new mural painting class conducted by Heinz Lohmar. He chose Lohmar over Hans and Lea Grundig, who at the time were the most prominent teachers in Dresden but, from Richter’s perspective, had less to offer him. As Richter told Robert Storr in 2001, Lohmar was “a very interesting type, a little gangster.’” Born in 1900 in Troisdorf near Cologne, Lohmar, a Jew and a member of the Communist Party, had emigrated in 1933 to Paris, where he had been a minor surrealist. At war’s end, Lohmar returned to Germany to live in the Soviet-occupied zone. Even so, as Storr puts it, he “remained a comparatively well-informed and cosmopolitan figure.” In any event, Richter thought he could learn from him.

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 1–11 of Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting by Dietmar Elger, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2010 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Dietmar Elger

Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting

Translated by Elizabeth M. Solaro

©2010, 408 pages, 78 color plates, 103 halftones, 7×10

Cloth $45.00 ISBN: 9780226203232

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting.

See also:

- Our catalog of art titles

- Our catalog of biography titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog