Journey Maps

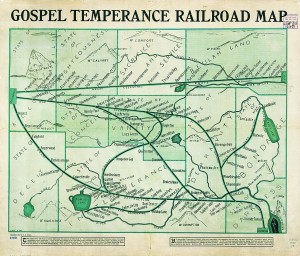

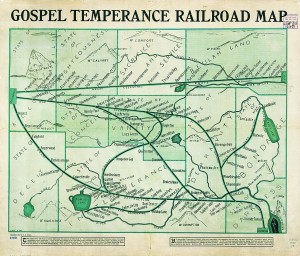

Gospel Temperance Railroad Map

|

G. E. Bula, "Gospel Temperance Railroad Map" (1908). Library of Congress.

|

The “Gospel Temperance Railroad Map” is an example of an allegorical map. It was published in 1908 by G. E. Bula and looks very much like the typical American railroad map of its day. It presents the traveler with three main lines diverging from Decisionville in the State of Accountability at the left-hand side of the map. The routes of the lower two lines, the Way That Seemeth Right Division and the Great Destruction Way Route, pass at first through towns representing relatively minor vices and self-deceptions of alcohol use, but lead inevitably to more serious “states” of Depravity, Intemperance, and Bondage. A River of Salvation offers hope for some, but those who stubbornly remain on the path of drink and debauchery end, without escape, in the City of Destruction. The upper line from Decisionville, the Great Celestial Route, is not without its trials, represented by such station stops as Bearingcross, Abandonment, and Long Suffering; but the final destination, The Celestial City, is clearly more desirable than its counterpart.

Photo-Auto Guide, 1905

|

Two pages from H. Sargent Michaels, Photo-Auto Guide, Chicago to Rockford (1905). Newberry Library.

|

Early motorists wishing to undertake long journeys relied extensively on published written itineraries known as route books. Like modern online or in-car services, these books provided turn-by-turn instructions, kept track of the passing miles, and took note of landmarks and hazards along the way. One variant of these itineraries, Photo-Auto Guides, supplemented their highly detailed directions with photographs of critical intersections and forks, so that motorists might be assured that they were indeed in the right place and had not missed their turn. By the mid-1910s serious efforts to mark and improve interstate routes were under way. Federal and state funds were committed to the effort, and by the late 1920s the entire country was fully committed to the construction of paved and well-marked highways. Network road maps of the type distributed at service stations became the normal type of road guide, while verbal route books largely disappeared.

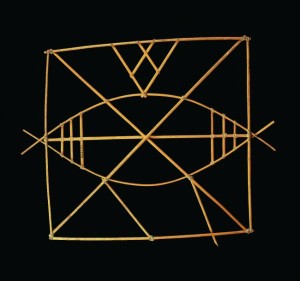

Marshall Islands Stick Chart

|

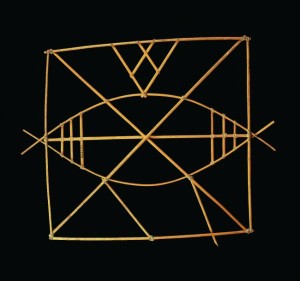

Marshall Islands stick chart (19th century). Field Museum.

|

Traditional sailing in the Marshall Islands relied especially on the islanders’ ability to read the patterns of ocean swells as indications of the proximity and direction to an island, because the prevailing currents in their island chain are especially variable and can easily deflect vessels off course if navigating by stars alone. Swells are broad undulations on the surface of the ocean that are generated by prevailing winds many miles distant (as opposed to smaller ripples and waves created by local winds). The Marshall Islanders recognized four main swells, each coming from a different direction, and they understood that the islands and their undersea slopes bend or refract these swells and reflect them. Then the swells pass over and through one another, creating noticeable high points in the water that are detectable by practiced eyes at some distance. Sailors visualized rays to connect these elevations and pointed their craft in the direction of the islands that caused them, leading the mariners to landfall. Understanding how these principles operate required a great deal of skill and experience, and the islanders developed stick charts to help novices learn this navigational system. The simplest of these,

mattangs, showed general patterns and principles. Others, called

meddos and

rebbelibs, were charts of specific island groups or of the entire Marshall Island chain. Locations of specific islands were marked by shells fixed to a lattice of wood, while the lattice indicated the general patterns of prevailing swells and their refraction around specific islands. Swells and rising and setting stars exist in other parts of the world, of course, but only in this environment of scattered islands and huge oceanic skies were the technologies for mapping them so necessary and well developed.

Mapa de Sigüenza

|

Mapa de Sigüenza (map formerly owned by Carlos de Sigüenza y Gongorra) (19th-century copy). Newberry Library.

|

Many communities of what is now central Mexico, including the Culhuas-Mexicas (Aztecs), created itinerary-format maps that recounted historic migrations. The most famous of these “itinerary histories” is the Mapa de Sigüenza (so called because it was once owned by the Mexican polymath Carlos Sigüenza y Góngora), which dates from the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. The story told by the map begins in the dominant scene at upper right. The winged god Huitzilpochtli instructs several Aztec elders to leave their homeland of Atzlan and migrate to the Valley of Mexico. The elders and a succession of leaders take the Aztecs on a journey of many years. Their path is marked in a traditional Mesoamerican manner of representing land routes, footprints walking on a double line. Along the way they stop at several cities indicated by hill glyphs, the usual sign for cities. Dots on the map indicate the number of years they remained in a particular city. Finally, the Aztecs reach the Valley of Mexico, subjugate local rivals, and settle in Tenochtitlan, represented by a cactus, in the center of the Lake Texcoco