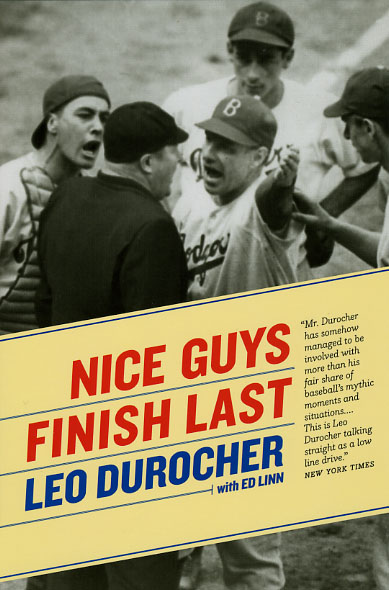

An excerpt from

Nice Guys Finish Last

Leo Durocher

I COME TO KILL YOU

My baseball career spanned almost five decades—from 1925 to 1973, count them—and in all that time I never had a boss call me upstairs so that he could congratulate me for losing like a gentleman. “How you play the game” is for college boys. When you’re playing for money, winning is the only thing that matters. Show me a good loser in professional sports, and I’ll show you an idiot. Show me a sportsman, and I’ll show you a player I’m looking to trade to Oakland so that he can discuss his salary with that other great sportsman, Charley Finley.

I believe in rules. (Sure I do. If there weren’t any rules, how could you break them?) I also believe I have a right to test the rules by seeing how far they can be bent. If a man is sliding into second base and the ball goes into center field, what’s the matter with falling on him accidentally so that he can’t get up and go to third? If you get away with it, fine. If you don’t, what have you lost? I don’t call that cheating; I call that heads-up baseball. Win any way you can as long as you can get away with it.

In the olden days, when I was shortstop for the Gas House Gang, I used to file my belt buckle to a sharp edge. We’d get into a tight spot in the game where we needed a strikeout, and I’d go to the mound and monkey around with the ball just enough to put a little nick on it. “It’s on the bottom, buddy,” I’d tell the pitcher as I handed it to him.

I used to do it a lot with Dizzy Dean. If he wanted to leave it on the bottom, he’d throw three-quarters and the ball would sail—vroooom! If he turned it over so that the nick was on top, it would sink. Diz had so much natural ability to begin with that with that kind of an extra edge it was just no contest.

Frankie Frisch, our manager and second-baseman, had his own favorite trick. Frank chewed tobacco. All he had to do was spit in his hand, scoop up a little dirt, and twist the ball in his hand just enough to work a little smear of mud into the seam. Same thing. My nick built up wind resistance on one spot; his smear roughed up a spot along the stitches, and the ball would sail like a bird.

We used to do everything in the old days to try to win, but so did the other clubs. Everybody was looking for an edge. If they got away with it I’d admire them. After the game was over. In a week or two. When Eddie Stanky kicked the ball out of Phil Rizzuto’s hand in the opening game of the 1951 World Series I thought it was the greatest thing I’d ever seen. Not because it was the first time I’d seen it done, but because it was my man who was doing it. Before the 1934 World Series began, the St. Louis scouting report warned us that Jo-Jo White of the Detroit Tigers was such a master at it that he would sometimes go all around the bases kicking the ball out of the fielders’ hands. Sure enough, the first chance he had, he kicked the ball out of Frankie Frisch’s glove and practically tore his uniform in half. A couple of innings later, Jo-Jo was on first again. “I got him,” I told Frank.

“No you don’t,” Frisch said. “He’s mine. I’ll get him; you step on him.”

White came into second, and while Frank was rattling the ball against his upper incisors I was dancing a fandango all over his lower chest. I guess Jo-Jo was no aficionado of the Spanish dance because he did nothing at all during the rest of the Series to encourage an encore. Or maybe he just didn’t like the idea of having to make an appointment with his dentist every time he slid into second base.

When my man Stanky does it, he’s helping me to win. When their man White does it, he’s helping them. I can’t be any more explicit about it than to say that you can be my roommate today and if I’m traded tonight to another club I never saw you before if I’m playing against you tomorrow. You are no longer wearing the uniform that has the same name on it that my uniform has, and that makes you my mortal enemy. When the game is over I’ll take you to dinner, you can have my money and we’ll have some fun. Tomorrow, you are my enemy again.

The Nice Guys Finish Last line came about because of Eddie Stanky too. And wholly by accident. I’m not going to back away from it though. It has got me into Bartlett’s Quotations— page 1059, between John Betjeman and Wystan Hugh Auden—and will be remembered long after I have been forgotten. Just who the hell were Betjeman and Auden anyway?

It came about during batting practice at the Polo Grounds, while I was managing the Dodgers. I was sitting in the dugout with Frank Graham of the old Journal-American, and several other newspapermen, having one of those freewheeling bull sessions. Frankie pointed to Eddie Stanky in the batting cage and said, very quietly, “Leo, what makes you like this fellow so much? Why are you so crazy about this fellow?”

I started by quoting the famous Rickey statement: “He can’t hit, he can’t run, he can’t field, he can’t throw. He can’t do a goddamn thing, Frank—but beat you.” He might not have as much ability as some of the other players, I said, but every day you got 100 percent from him and he was trying to give you 125 percent. “Sure, they call him the Brat and the Mobile Muskrat and all of that,” I was saying, and just at that point, the Giants, led by Mel Ott, began to come out of their dugout to take their warm-up. Without missing a beat, I said, “Take a look at that Number Four there. A nicer guy never drew breath than that man there.” I called off his players’ names as they came marching up the steps behind him, “Walker Cooper, Mize, Marshall, Kerr, Gordon, Thomson. Take a look at them. All nice guys. They’ll finish last. Nice guys. Finish last.”

I said, “They lose a ball game, they go home, they have a nice dinner, they put their heads down on the pillow and go to sleep. Poor Mel Ott, he can’t sleep at night. He wants to win, he’s got a job to do for the owner of the ball club. But that doesn’t concern the players, they’re all getting good money.” I said, “you surround yourself with this type of player, they’re real nice guys, sure—‘Howarya, Howarya’ and you’re going to finish down in the cellar with them. Because they think they’re giving you one hundred percent on the ball field and they’re not. Give me some scratching, diving, hungry ballplayers who come to kill you. Now, Stanky’s the nicest gentleman who ever drew breath, but when the bell rings you’re his mortal enemy. That’s the kind of a guy I want playing for me.”

That was the context. To explain why Eddie Stanky was so valuable to me by comparing him to a group of far more talented players who were—in fact—in last place. Frankie Graham did write it up that way. In that respect, Graham was the most remarkable reporter I ever met. He would sit there and never take a note, and then you’d pick up the paper and find yourself quoted word for word. But the other writers who picked it up ran two sentences together to make it sound as if I were saying that you couldn’t be a decent person and succeed.

And so, whenever someone like Ara Parseghian wins a championship you are sure to read, “Ara Parseghian has proved that you can be a nice guy and win.” I’ve seen it a thousand times. They don’t even have to write “Despite what Leo Durocher says” any more.

But, do you know, I don’t think it would have been picked up like that if it hadn’t struck a chord. Because as a general proposition, it’s true. Or are you going to tell me that you’ve never said to yourself, “The trouble with me is I’m too nice. Well, never again.”

That’s what I meant. I know this will come as a shock to a lot of people but I have dined in the homes of the rich and the mighty and I have never once kicked dirt on my hostess. Put me on the ball field, and I’m a different man. If you’re in professional sports, buddy, and you don’t care whether you win or lose, you are going to finish last. Because that’s where those guys finish, they finish last. Last.

I never did anything I didn’t try to beat you at. If I pitch pennies I want to beat you. If I’m spitting at a crack in the sidewalk I want to beat you. I would make the loser’s trip to the opposing dressing room to congratulate the other manager because that was the proper thing to do. But I’m honest enough to say that I didn’t like it. You think I liked it when I had to go to see Mr. Stengel and say, “Congratulations, Casey, you played great?” I’d have liked to stick a knife in his chest and twist it inside him.

I come to play! I come to beat you! I come to kill you! That’s the way Miller Huggins, my first manager, brought me up, and that’s the way it has always been with me.

I’m just a little smarter than you are, buddy, and so why the hell aren’t you over here congratulating me?

After the Dodgers had lost the final playoff game to San Francisco in 1962, I couldn’t even bring myself to do that. And I wasn’t even the manager, I was only the coach. Still, I should have been the second Dodger over there, right behind Walter Alston. Alvin Dark, the Giants’ manager, was one of my boys. He had played for me and he had been my captain. Many of the Giants players were close friends, and there was Willie Mays, who is as close to being a son as it is possible to be without being the blood of my blood and the flesh of my flesh.

But, dammit, we had gone into the ninth inning leading by two runs. With the ball club we had, we should have run away with the pennant. All right, that’s baseball. I could remember that Jackie Robinson, whom I had been feuding with all year, had been the second Dodger player in our locker room in 1951 after we had beaten them on Bobby Thomson’s home run. I knew Jackie was bleeding inside. I knew he’d rather have been congratulating anybody in the world but me. And still Jackie had come in smiling.

But I sat there without taking off my spikes, and I just couldn’t do it. We had lost with one of the best teams I had ever been associated with. My kind of team. This was the year Maury Wills stole 104 bases and won the Most Valuable Player award. Tommy Davis, who hadn’t broken his ankle yet, had the most incredible year in modern baseball. (Would you believe .346, 230 base hits and 153 rbi?) Plus 27 home runs. Willie Davis, who could outrun the world, had 21 home runs and 85 rbi. Frank Howard was giving us the long ball, 31 home runs and 119 rbi. And good pitching. Don Drysdale was having the best year of his life, 25 victories and the Cy Young award. Sandy Koufax had been going even better until he was knocked out by a circulatory blockage in his finger shortly after the All Star game. And still Koufax led the league in Earned Run Average. Ed Roebuck was having a fabulous year in relief.

Seven key players having the best seasons of their career, and we couldn’t shake the Giants. Three guys who could run like ring-tailed apes, and we had a manager who sat back and played everything conservatively. Forget the signs. Speed overcomes everything. Let them run.

After Koufax went out, I just thought, To hell with it. Alston would give me the take sign, I’d flash the hit sign. Alston would signal to bunt, I’d call for the hit-and-run. They were throwing the first pitch right in there to Maury Wills, knowing he was willing to get on with a walk. “Come on,” I told him. “Swing at the first one, don’t let them get ahead of you. You’re not just a runner, you’re a hitter. Rip into it.” Goddam, when he wasn’t bouncing the ball over the third baseman’s head he was ripping line drives down the right-field line, something he had never done before. I was letting him hit on the 2-0 and 3-1 counts, something he had never done before either. The more he hit, the more he ran, and before you knew it his fielding had got better. I never “saw” a take sign from Alston with any of the speedsters—and how they loved it. The whole team knew what I was doing, and they were saying, “Just keep going, Leo. Goddam, we never played like this before. It was always played tight to the vest around here before but now, Christ, we're playing wide open.”

All that talent wanting nothing more than to express itself. The players were so loose; oh, God, that’s the way it’s supposed to be, everybody laughing, everybody relaxed. We won 17 out of 21 games and took a 5½-game lead with maybe five or six weeks to go. And then we lost two games in a row and Alston called a meeting. “As of tonight, starting with this ball game,” he said, “I will take complete charge of this ball club. And Leo, that means you. If I give you the bunt sign, that’s what I want. The bunt. And if I give you the take sign, I want that hitter to take. Any sign that I give and you miss,” he said, “I will fine you two hundred dollars and the player at bat two hundred dollars.”

There was not a thing I could do any more. “I’m gone, fellows. All can do is stand there like a wooden Indian and give you the signs. If he gives me the bunt you got to bunt. Because it won’t just be me who’ll be fined if you don’t. You’ll be fined, too.

And, boy, he took the bats right out of their hands. He took the bats out of their hands and, brother, their assholes tightened so that you couldn’t drive a needle up there. In the pressure of a pennant race you can really tighten them up, and the tighter they got the more conservative he became.

And every day he held a meeting, which is the worst thing you can do when a team is going very bad or very good. If they’re going good, who needs a meeting? “Just keep going, fellows,” that’s all the meeting you need. If they’re going bad, you can only look for the opportune moment to relax them.

Whenever I held a meeting on a team that was that tight it would be to say, “Come on, for chrissake, you’re playing like a lot of two-dollar whores. Swing the bat if you hit the ball ten feet in the air. If I didn’t know you fellows and I wasn’t seeing it, I wouldn’t believe this. I know you’re a good ball club, what the hell are you doing? Come on, let’s slash and rip at ’em. And no curfew tonight. Go out and get drunk. I don’t care what you do. Just show up at the park in time for tomorrow’s game.”

Every day Alston would hold a meeting and go over the opposition. You know what they say at meetings? On seven of the eight starters, they say, “Push him back and curve him on the outside.” The eighth guy is hitting .220 and they say, “Throw it by him.”

Day by day it got worse and worse. The only reason we didn’t blow the lead was that San Francisco was losing right along with us. With eight games left we were still four ahead. We lost four out of five—couldn’t score a run—and with three games left we were two ahead. All we had to do was win one of them. We lost all three. With a team like that, it was criminal.

In the third game of the playoff series, we were leading by two runs in the last of the ninth. And that was the inning that almost got me fired.

Ed Roebuck had come into the game in the sixth inning and pitched out of a jam. Got by the seventh and struggled to get through the eighth. Pitching has always been one of my strong points, and I could see that his arm was hanging dead. “How do you feel, buddy?” I asked him, as he was coming off.

He said, “My arm feels like lead. Man, I am tired.”

I didn’t go to Alston. I went to the pitching coach, Joe Becker, who was standing practically alongside him at the corner of the dugout near the bat rack. That’s the right way to do it. You don’t go over the pitching coach’s head. “Get somebody ready,” I said to Becker. “Don’t let this fellow go out in the ninth inning. He can’t lift his arm.”

Becker didn’t say a word. Alston didn’t say a word. It was like I wasn’t there.

I said, “Walt, he told me he was tired. He’s through.” And Alston said, more to Becker than to me, “I’m going to win or lose with Roebuck. He stays right there.”

All right, I went out to the third base coaching box, we got the bases loaded with two out and Roebuck is supposed to be the hitter. I was so sure Alston was going to send up a pinch hitter, that I was making hitting motions from the coaching line. And here comes Roebuck out of the dugout with his batting helmet on.

When I came back in and took my seat at the other end of the bench, Drysdale, Koufax and Johnny Padres—who had started the game—were standing right there. “Don’t let them send Roebuck back out,” they pleaded. “Tell him he’s got to make a change. Don’t let him do it, Leo.”

“Don’t let him? What the hell do you want me to do, I’m not managing the club. There’s not a goddam thing more I can say than I’ve said.”

Worst inning I ever saw in my life. The first batter singles, and he’s forced at second. One out. And now Roebuck is so tired that his control deserted him. He walked Willie McCovey, who was pinch-hitting, and then he walked Felipe Alou. The bases are loaded and here comes Willie Mays. Alston didn’t make a move and I’ll be a sonafagun if he almost didn’t get away with it. Willie hit a bullet back at Roebuck. Waist high, practically into his glove. If it had stuck it probably would have been a double play. As it was, the ball was hit with such force that it tore the glove right off his hand. A run was in and the bases were still loaded, but we were still one run ahead.

And now Walt called me over from the other side of the dugout to make a pitching change. When I got to the batrack, he said, “Bring in Williams.”

I put one foot up on the bench and I hollered back, “What? Did I hear you right? You’re bringing in Williams?”

“That’s what I said. Williams.”

Stan Williams was a big, wild right-hander. He had pitched very well toward the end of the season, but in a spot like this? Williams?

I went out and I brought in Williams, and then I said to the boys on the bench, “We may as well go in. If I had ten pitchers this would be the tenth one I’d bring into a spot like this. He’ll walk the ball park.”

Orlando Cepeda hit a long fly to right field bringing in the tying run and advancing Felipe Alou to third.

Two out. Men on first and third, and, sure enough, Williams uncorked a wild pitch that Roseboro was able to block just enough so that only Mays could advance. With men on second and third, Alston ordered an intentional pass to load the bases again. Nobody on the bench said a word. Nobody had to. The same thought was on everybody’s mind. He’s loading the bases with Williams pitching, and right after Williams has shown that he hasn’t got his control.

Another walk is going to bring in the winning run.

Williams walked Jim Davenport.

Kiss the pennant goodbye.

I wasn’t the only one slumped at my stool after the game. The players told the clubhouse man to lock the door, and while Alston was over in the San Francisco dressing room congratulating Dark, something happened that I had never seen in any clubhouse or ever expected to see. Where they came from I will never know, but whiskey bottles were handed around to the players. For almost an hour, they sat there, stunned. Except for an occasional shouted curse, nobody said anything. They sat like I was sitting, in their sweaty uniforms, and tried to get themselves drunk.

Three hours later, I did manage to heave myself over to the Grenadier Restaurant, which was run by the same man who ran the Stadium restaurant at Chavez Ravine. A party had been scheduled for the Dodger officials, and while neither Mr. O’Malley nor Mr. Bavasi showed up, almost everybody else connected with the club did. The hilarity, as you might well imagine, was restrained.

During the course of these solemn rites, I was called over to the big table where most of the Dodger officials were seated. By then, everyone had had a few drinks and, although I am not normally much of a drinker, I’d had a few myself. While we were commiserating with each other, someone at the table said to me, “If you’d have been managing the ball club, we’d have won it.”

I just looked this man right in the eye and I said, “Maybe.” And then I said, “I know one thing. I’d have liked to go into the ninth inning with a two-run lead. I’d take my chances.” Period. End of quote.

That’s all said. It wasn’t exactly a call to mutiny and it wasn’t exactly the most revolutionary idea since the movies discovered sound. Who wouldn’t like to go into the ninth with a two-run lead? And, you will notice, I hadn’t called a press conference to say it. I was replying to a question put to me, among friends, at a time when everybody had been drinking.

It didn’t come out that way in the newspapers, though. The way the papers had it, I had publicly second-guessed Alston. The way the newspapers had it, I had said that if I had been the manager we’d have won the pennant.

Buzzy Bavasi, the Dodger's general manager, read the reports and told the newspapers that if I had said those things I was fired. When I was finally able to get him on the phone, he said, “Well, I see you were popping off again.”

I said, “Who popped off, me or you? Why didn’t you call me, Buzz? Why didn’t you ask me if I said what they printed? I wouldn’t have lied to you. If I’d have second-guessed Alston I’d have told you I second-guessed Alston. So what? You’d have fired me. That’s the worst you could do to me.”

Buzzy, not quite convinced, told me he was going to check my version out. A couple of nights later, I met him at a Friars Club stag for Maury Wills. His investigation, he said, had backed me up in every detail. “Buzz,” I told him. “I’m surprised at you. You gave me an awful going over.”

“Well” he said, “I was mad.”

“I’ll tell you something,” I said. “I didn’t feel too good that night myself.”

Everybody was disappointed and so they pounced upon the one thing that had come to land—a distorted story about Durocher. And so Durocher was up the creek again, a neighborhood I have come to know rather intimately through the years.

I will admit, however—if you press me hard enough—that I had said just enough to bring on everything that happened. I’ve been in that neighborhood before, too. Branch Rickey once said of me that I was a man with an infinite capacity for immediately making a bad thing worse.

Carve it on my gravestone, Branch. I have to admit it’s sometimes true.

As far as Rickey was concerned, I was sometimes able to make a bad situation worse even when I’d have sworn I was making it better. During the last year of the war, when the Dodgers were playing anybody who could fit our uniforms, one of the fittees was Tom Seats, a left-handed pitcher who had labored through the years in the minors, not wholly without success. A year earlier, he had been doing his bit by working in an airplane factory in San Diego. Pitching only over the weekend, he had won 25 games in the Pacific Coast League.

For us, he couldn’t get by the third inning. Over and over it happened—I couldn’t understand it. He was strong as a bull; he had a good curve; his control wasn’t that bad. And he kept getting his jock knocked off.

Charlie Dressen, who could get information about everybody, finally came to me and said, “You know, Leo, they tell me this guy drinks. Can you get any whiskey around here?”

That was a good question. Whiskey was in such short supply by then that not even Mac Kreindler of “21,” who had been a good friend of mine from back in the old days, could get any for me. The best he could come up with was two dozen of those little half-pint bottles of brandy.

Just before Seats was ready to warm up for his next start, I invited him into my office for a man-to-man talk. “Tom,” I said, “you’ve got to be a better pitcher than you’re showing me. You can’t win twenty-five games against nine girls unless you’re a better pitcher than this.”

He didn’t have the slightest idea what was wrong. All he knew was that he didn’t seem to have any strength when he went out there.

I said: “I know you drink.”

“I sure do.”

I asked him if he drank brandy.

“I drink anything,” he said.

Out of my desk came one of the little bottles of brandy. As I poured him a shot, his eyes got that big. He took one gulp, and I could see that the next time I wouldn’t have to worry about the glass. He warmed up, and I want to tell you something; by the time the game was ready to start the brandy was pouring out of him. That sonofagun pitched five scoreless innings. They couldn’t touch him. And then I took him into the clubhouse, let him get into a dry uniform and gave him another big belt.

From there on in he was the best pitcher we had.

At the end of the season, Mr. Rickey called me into his office for the specific purpose of congratulating me on the fine job I had done with Tom Seats. “I have never seen such a transformation,” he said. “From a Class C pitcher to a fine major-league pitcher. I don’t know what you said or did to the man, but whatever it was I’d like to hear it from you.”

I said, “Well, Mr. Rickey, I gave him a shot of brandy—about this much—twenty-thirty minutes before he warmed up. And then I gave him another shot in the fifth inning.”

Rickey’s eyebrows always seemed to become twice as thick when he was angry. He just kept staring at me, and then his eyes began to squint, and I knew I was in trouble.

“You … gave … a … man … in … uniform … whiskey?”

I didn’t think he’d appreciate the distinction between whiskey and brandy, and so all I said was, “Yes, sir.”

He said: “He will never pitch again for Brooklyn.” His eyes got even smaller. “I should fire you right now.”

I was in trouble, all right. “Mr. Rickey,” I said. “I thought when I signed the contract I signed for one thing. There is a ‘W’ column and there is an ‘L’ column. I thought it was my obligation and duty to put as many as I could under that ‘W’ column. I saw nothing unethical about what I did. I just gave a man a little drink of brandy. I think it gave him more confidence, loosened him up. It must have done something, Mr. Rickey, or he couldn’t have had what you just called such a transformation. Now what it was, Mr. Rickey, I don’t know. But it certainly got the job done.”

Branch didn’t buy the medicinal angle at all. Seats never pitched another game in the major leagues, and I never came closer to losing my job.

As long as I’ve got one chance to beat you I’m going to take it. I don’t care if it’s a zillion to one. As long as I can be on the ball field with you I have a chance. In 1954, the year I won my second pennant with the Giants, we were playing the Dodgers late in the year, at a time when they were making a run at us. We won the first one, and in the second game, Carl Erskine had me beaten, 5-4, in the ninth. We had the bases loaded with two out, and Wes Westrum, my catcher, was coming to bat. Poor Wes was in a horrible slump. He was only playing because we had no other catcher. The way he was going he couldn’t have hit me if I ran by slow and ducked a little bit. I called time and yelled for Dusty Rhodes, who was having the greatest season any pinch hitter has ever had. Before Dusty took two steps, my coaches came running in from first and third, and Frank Shellenbach, my pitching coach, was on the phone from the bullpen.

“You can’t do that, Leo,” they were all shouting. “You have no catcher.”

And Rhodes is hollering. “He don’t need a catcher. Don’t worry about it, I’ll win it right here.”

I called Westrum back, and I told Rhodes there was an automatic $200 fine if he walked or got hit by a pitch. “I can’t stand a tie score, Dusty,” I said. “You got to hit the ball. I don’t care if you hit it ten feet straight up over home plate. But swing.”

The first pitch Erskine threw was a high change-up, which Dusty always had a tough time with. He started to swing nine different times, and almost fell on his face. The next pitch was a high, fast ball, and Dusty hit a bullet into center field and won the ball game.

Back in the clubhouse the newspapermen gathered around me. What would have happened if he’d walked or got hit? Or got on with an error? “You’d have had no catcher, did you think of that?”

Yeah, I’d thought of it. And I’d also thought that I’d rather be in the tenth inning without a catcher than in the clubhouse with a loss. “Once I’m in the clubhouse and the door is locked I can’t win it. As long as I’m out on that green stuff out there, playing against you, I’ll find somebody to catch.”

I’d have found somebody, and if we had lost on a passed ball they’d have been calling me the dunce of all time.

I’ve been called that before, too. If you’re afraid, go home.

How badly do I want to win?

During my early years as a manager, some guy got up at a banquet after I had spoken and kept asking me that same question. Nothing I said seemed to satisfy him until, finally, the perfect illustration flashed into my mind. “If I were playing third base and my mother was rounding third with the run that was going to beat us,” I told him, “I would trip her. Oh, I’d pick her up and I’d brush her off, and then I’d say, ‘Sorry, Mom.’ But nobody beats me!”

I was on my way home for a visit and, just my luck, they wrote up that part of it in the paper. My mother was a little woman, and while she knew nothing at all about baseball she knew enough to know that she didn’t relish the idea of being tripped by her youngest son. She was ready for me as soon as I walked through the door. “You said that about your own mother? You’d trip me, son, your own mother?”

I tried to explain that it had only been a figure of speech, that it was just an illustration I had picked out of the air as a way of showing this man how far I would go to win.

She looked at me, and her eyes bugged out. “Then you would have tripped me,” she screamed. “You would have tripped me. You would! You would!”

For the rest of my visit, she walked around with an injured

air. And I guess she had a right to. God rest your soul,

Mom, I’m afraid I would.

![]()

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 11–26 of Nice Guys Finish Last by Leo Durocher with Ed Linn, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©1975 by Leo Durocher. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press.

Leo Durocher with Ed Linn

Nice Guys Finish Last

©1975, 448 pages

Paper $18.00 ISBN: 9780226173887

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Nice Guys Finish Last.

See also:

- An excerpt from Veeck—As In Wreck: The Autobiography of Bill Veeck

- Our catalog of biography titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog