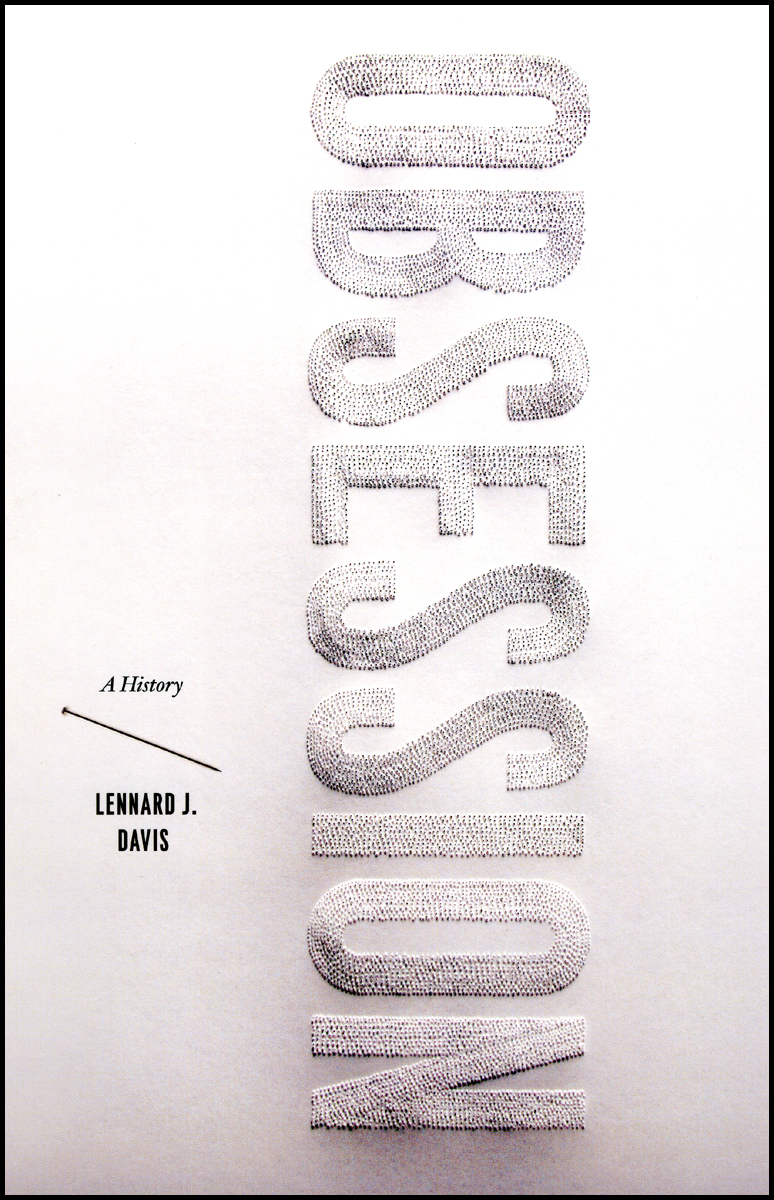

An interview with

Lennard J. Davis

author of Obsession: A History

Question: Most of us think of think of disease as being timeless, but you argue that obsession is a modern condition—from the democratization of madness in the eighteenth century to the anxiety about safety and cleanliness that haunts OCD-sufferers. How has obsession been recast as a pathology rather than a harmless eccentricity?

Lennard J. Davis: It’s important for me to say at the outset that I do think OCD is a real disease and that it causes pain and suffering to many of those who have been diagnosed with this disorder. That being said, I think we also have to remember that psychiatric disorders have a relatively short half-life. We have seen many become obsolete, and we’ve see the resurgence or invention of many others. My book traces the fluctuations of the Western world’s interest in obsession—both as a cultural goal and feature of modernity and as a pathology. There is a smug comfortableness in psychiatric circles with the idea that OCD and obsession are two entirely different things.

What I try to show in this book is that there is a continuum between OCD and other kinds of obsessive behavior in our society. The firewall between the pathology and the behavior has been set up to be impervious, but I think we can learn a lot more not only about OCD but the way we categorize and delimit psychiatric disorders if we allow a flow from the harmless eccentricity to the serious illness, from the growth of obsession as a cultural category to the rise of the disease.

Q: Obsession, as you define it, is both a cultural activity and a brain disorder. Does obsession lie on a continuum with, on one end, say, a fixation and on the other clinical OCD? Or are they unrelated, grouped together only by the use of the same word to define the condition?

Davis: Again, the standard psychiatric diagnosis would not allow for a linking up of the cultural activity and the brain disorder. The need to be separated for dianostic and professional reasons. But this is a bit like saying that war between countries is one thing and fighting between people is another. It’s true there is much to be gained in the study of war, but we lose the continuity between human violence and aggressivity. Any time we delimit for professional reasons, we lose another viewpoint or perspective. So as a cultural historian, I’m arguing that I can provide a wider and more expansive view of OCD’s relation to other cultural formations than can a clinician. I’m not saying that for the purposes of treatment and so on the clinician is wrong, but I’m saying that his or her viewpoint will necessarily be limited by the utilitarian nature of their profession. I’m arguing that a biocultural perspective may yeild a great trove of knowledge than a more narrow clinical one.

Q: You note that incidences of OCD have gone from one in twenty thousand to one in ten in less than thirty years. Does this mean more people actually have the disease or it is suddenly fashionable—much like the democratization of madness you describe in the eighteenth century—to claim to be afflicted?

Davis: To me this is the “tell” that reveals the problem with contemporary psychiatry. If OCD is a brain disease that has always been around and is therefore relatively independent of culture, then how can the brain scientists explain the meteoric rise in the incidence of the disorder? Neurobiological and neurochemical explanations tend to see the brain as a structure that is universal in all cultures and at all times. But we have the evidence that obsessive behavior has shape-shifted through several different disease nosological categories over the past 300 years. Not only has it had different names and explanations, but it went from a rare disease to the fourth most common psychiatric disorder in the world, according to the World Health Organization.

The explanations provided by experts in the field is that more people are comfortable coming forward as the disease becomes better known. But that could only be a partial explanation at best, given the numbers. Rather, as we’ve seen with other diseases that have gone from rare to common—ADD, Social Anxiety Disorder, anorexia, and so on—there is a complex mix of cultural, economic, and even political factors. The involvement in drug and insurance companies in the genesis and ramping up of such conditions into mega-epidemic plagues is not to be underestimated. And of course, in the notion of a democratization of madness, we’ve come to expect that to be human means to have one or two of these popular disorders. There isn’t a person I’ve ever met who didn’t acknowledge that they were neurotic, and many people can’t wait to share with me their “OCD”-like behaviors.

Q: Why are we living in a golden age of obsession? If, as you show, the disease has been around in one form or another for hundreds of years, why are we seeing such huge numbers of cases of clinical obsession right now?

Davis: Many drug companies have developed SSRIs that have been approved in the treatment of OCD—a disease by the say that was very intractable and resistant to cure. Psychiatric iseases tend to proliferate, paradoxically, when there is a new cure. The appearance of SSRIs triggered the huge uptick in the number of people with depression. Ritalin did the same for ADD. So we can’t underestimate the significance of the role of drug companies. But I think there is something more. We are increasingly surrounded by a world that demands obsessive behavior. We now can check our emails addictively with our IPhones and PDA’s. We can watch the elections with an obsessive attention that we didn’t have before—with instant checks on the Internet, and a TV industry geared to create a panic at a moment’s notice. If you miss checking your blogs and your on-line sources, you can be out of the discussion. In our careers, we are required to spend inordinate amounts of time devoted to doing one thing, and that itself is both the cause and the symptom of OCD—doing or thinking about one thing too much. Yet, we get rewarded for doing that in our careers. It’s hard to imagine that in a culture that values this kind of behavior you wouldn’t have some people who are the outliers in these activities who end up suffering and paying for the obsessive profligacy of the society as a whole.

Q: There is no cure for OCD and treatment response hovers around 35%, just a few points higher than placebo. How does your book seek to change the way we treat OCD?

Davis: Let me make it clear that I am not an MD or a practioner so I can’t really affect clinical practice. Yet, I’m suggesting that if we let practioners and their patients know that this disorder is a complex one that has a history, we might be able to de-pathologize it a bit. Just as disability has gone from a medical pathology to a poltical identity, what could we do to depathologize some psychiatric conditons? Organizations of psychiatric survivors or consumers, as they call themselves, are trying to recast the rigid and draconian diagnoses made by clinicians into more subtle and livable ones. Groups like Mind Freedom or the Icarus Project. Intervoice, Hearing Voices Network all seek to revision mental illness, manic-depression, and schizophrenia into conditions that are not stigmatized, can be seen as empowering, and that are culturally and socially relevant. This isn’t to say that they or I eschew advances in neurobiology or neurochemistry. Many of the people in these organizations are dependent on an interaction between themselves and clinicians, particularly in the realm of taking psycho-pharmaceuticals. So, along with these groups, I am advocating a savvy, consumer driven approach to OCD that would allow for people with OCD to see themselves as part of a long and distinguished history rather than simply those assigned a diagnosis and given a treatment regimen.

Q: You mention in your introduction that, as a child, you exhibited symptoms of OCD? Do you still?

Davis: I think I’ve done a nice job of illustrating my thesis. I’ve taken my OCD symptoms as a child—checking, desire for symmetry, and so on—and turned them into socially useful things like being very on top of my email, very up on news and information, very interested in food and the presentation of food, and most importantly I am a workaholic and a prolific writer. So in that sense, I’m the poster boy for the argument that the line between pathology and culturally accepted forms of the same exact behaviors is a very permeable boundary.

Q: Then, at the end of the day, couldn’t the argument be made that we are all obsessed?

Davis: Actually, I think that not everyone is obsessed. And that can be a problem in a culture that values obsession. The slackers and the depressed can be seen as a particular problem in a society that is focussed on obsession … that is obsessed with obsession. This is why obsession becomes such a problem—you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t. Slackers and students with learning disabilities aren’t obsessed enough and housewives cleaning their floors ten times a day are too obsessed. The problem in the end is to describe this disease of modernity and then find some kind of Aristotelian mean for being obsessed. But, of course, that could itself become a new obsession.

![]()

Copyright notice: ©2008 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press.

Lennard J. Davis

Obsession: A History

©2008, 296 pages, 17 halftones

Cloth $27.50 ISBN: 9780226137827

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Obsession.

See also:

- Our catalog of books in medicine

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog