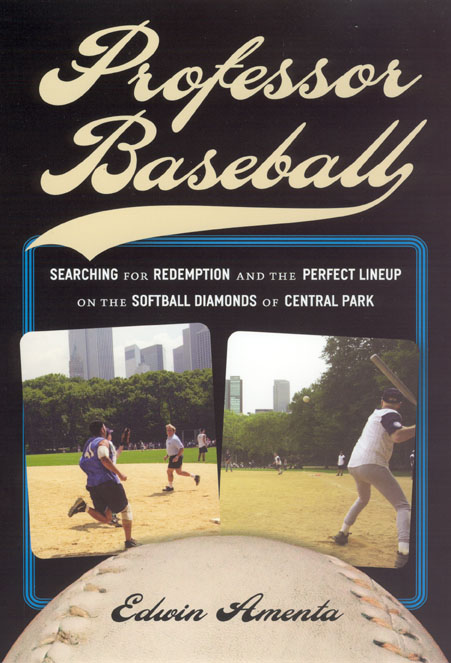

Episodes from

Professor Baseball

Searching for Redemption and the Perfect Lineup

on the Softball Diamonds of Central Park

Edwin Amenta

Call me Eddy.

I’m not your average baseball-loving professor. Unlike the sweater-wearing talking heads who wax poetical in front of Ken Burns’s cameras, I’m going to be playing ball in New York City this summer, probably on five softball teams. Even at my age, I’m still trying to prove myself. My ball-playing career has been checkered at best. I had a great season as a nine-year-old. I was the team’s top hitter, threw a no-hitter, and played shortstop or catcher when I wasn’t pitching.

But then the other kids grew. I didn’t. The next season I got no hits whatsoever, waving hopelessly at heaters unleashed by kids with precocious pituitaries. I plunged from superstar to mascot. It didn’t get better … until last season, when, well past my prime, I was discovered as a softball player. Getting onto an organized team in Manhattan is next to impossible. There are tens of thousands of potential players but only about five places to play. To top it off, anyone who is invited onto a team is, usually, in for life. It’s less like a dugout pass than an appointment to the federal bench. And I was in.

Spring is here again. With a new season of softball, I have a rare opportunity. How many of us have wanted to redo something we failed at as children? So this season I am going to play softball nearly every day and twice on Sundays; I’ll also be managing a team. This may be my last chance to avenge my Little League humiliation.

Play ball.

Cartwright and Me

My chance to show that I can run things in softball goes beyond team Pamela’s Cantina. I also hold a permit for Greenwich Village Adult Softball, a group that has been playing pickup ball since the 1980s on James J. Walker Field, a West Village Little League park a tape-measure home run away from the Hudson River. We call the field J. J. Walker, as if were named not for the Jazz Age mayor but for the Good Times star who bestowed upon our nation the exclamation “Dy-no-mite!” J. J. is so tiny that balls lifted over the outfield fence are counted as outs. A makeover to artificial turf a few years ago put J. J. temporarily out of commission. Aside from Central Park, New York’s parks are bucking the major leagues’ ineluctable return to natural grass. (The Astrodome, once called the eighth wonder of the world, has been put out to pasture, and now only the ridiculous Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome has artificial turf.) The pickup game moved to the afternoon and three miles away to East River Field #2, which spreads out below the Williamsburg Bridge at Grand Street. Since then, East River #1 and #2 have also been converted to artificial turf.

When our league’s commissioner resigned, I had volunteered to pitch in, filing the application at the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation on West Sixty-First Street and writing a check for twenty weeks’ worth of field—from four to seven o’clock every Saturday afternoon through Labor Day. I also bought twenty new de Beer Clinchers, New York’s soft softball of choice. A larger model of this ball is used by Chicagoans, who play with bare hands. If you ever roll out, even for batting practice, a Dudley, Worth, Red Dot, or any of the other hard softballs the rest of the country relies on, New Yorkers, tough guys all, will throw it aside and admonish you, “Are you crazy? Somebody could be killed with that rock!” All told, I was out of pocket more than eight hundred bucks.

The pickup game had been my only New York softball outlet for years. But more important, without this game I would never have been discovered by the players in the organized leagues. In the wide-open spaces of East River #2, Billy noticed that I could track down fly balls. And I would not have been playing at East River to be discovered, if not for something that happened several years earlier, when J. J. was a sandlot.

I had become a regular, but I didn’t get along with all of the longtime regulars. Something about my style may have rubbed some of them the wrong way. I play hard and want to win, and I like to move the games along. When I first started to play, there was extensive batting practice, as many as fifty swings per batter. Once the game started, there would also be about five minutes of infield practice every half inning. I couldn’t do much about BP but took aim at the between-inning delays. Local custom was that the batting team supplied an umpire, and I jumped at the chance. As soon as the defense was on the field, I would cry out, “Balls in, batter up!” In partial rebellion players began to mimic my trademark call, their voices cracking like teenagers, when they umpired.

For whatever reason, maybe an abiding attachment to infield practice, one longtime regular, Whitman, seemed to have it in for me. He ran about six-foot-two and 230 pounds, with long, dark hair, topped with a faded denim U.S. Postal Service cap, and an unkempt beard that grew best on his neck. A left-hander who had managed to harness his considerable power to keep his wicked liners within the confines of J. J., Whit seemed bottled up by the effort, and his frustration often seeped out in inappropriate base running. Whit was always a threat to do a Pete Rose into the catcher—whether man, woman, or child. But given his size and badass attitude, the most any of us ever did about it was commiserate. Several of us agreed that when reporters interviewed us after Whit had shot up the post office, we would dispense with the usual display of shock and tell them that we had seen it coming all the way.

One evening that summer, Whit was on first base, I was at shortstop, and the batter singled into center. Given the small dimensions of the field, I went to cover second in case there was a chance for a force play. The relay was late, and Whit was going to be safe with ease. He might have gone in standing up, as the throw was late. He might have executed a pop-up slide, in case the throw got away. But instead he opted for a takeout slide—complete with roll. In a double-play situation, middle infielders know a takeout could be coming and prepare to jump or sidestep. But on this play, my back was to the infield and his move blindsided me like a football clip.

I got to my feet and looked for support, but either no one else saw it or, more likely, no one who did wanted to get involved. Whit glared at me and by way of apology offered, “If you can’t take it, you shouldn’t try to play.” Taken together, my brush with injury, Whit’s unsympathetic reply, and everyone else’s resounding lack of response disengaged the car alarm that goes off in my head when I’m anywhere near placing myself in physical danger. I started screaming at him from my dangerously proximate shortstop position, “A takeout slide on a throw from the outfield? Do you have any idea how this game is played? Is there something wrong with you?” His only reply was a spurt of saliva.

I stayed upset for the entire week. As bad luck would have it—or maybe the captains picking the teams were entertained by the rivalry—we were opponents again the following Saturday night. This time I was playing second base. Whit was on first with nobody out when a grounder came my way. I stepped forward to tag him, hoping for a tag-out–throw-out double play. Trying to knock the ball free, Whit treated me to a forearm shiver—to my jaw. This belligerent play was way out of line and would earn a suspension in the Central Park leagues, and I would’ve gotten the double play too. But not here. I was holding my chin and trying to complain but could only squeeze out, “What the hell?” He gave me a dismissive look that all but called me a pussy. Since I had hung onto the ball, and, fortunately, my bicuspids, I was denied even the satisfaction of lecturing him on his primitive understanding of the game. I was starting to long for the more subtle abuse I had absorbed in Little League.

I tried to channel my anger into a plan of action. Picking a fight with him was, of course, out of the question. If I were going to get back at him, it would have to be in the flow of the game. And then I had it! In baseball, a runner who tries to break up a 4–6–3 double play stays down on the slide. The shortstop sidearms the relay to first, whizzing it right over the runner’s head to enforce the custom. Everyone in baseball knows this, and runners seldom get hit. In softball, however, no matter how high the slide, shortstops try to avoid the runner. I knew that Whit tended to slide on the high side, and if he wanted to play hardball with me, well, two could play at it. The next time he is on first and a grounder comes to second, I thought, I will take the relay at short and, if he doesn’t get way, way down, I will ricochet the scowl off his scraggly face. I fantasized about this frequently, rerunning this mental video clip, and was so satisfied with it that I could stand playing on the same field with Whit, almost always on the opposing team. “That’s right—you’d better get down,” I would say to myself and on occasion, disturbingly, aloud, as the weeks passed and I replayed the key footage. As with Whit’s going postal, I was certain that it was just a matter of time before I would exact vengeance and win justice.

One day late in August, the game was unspooling just as in my internal highlight reel. Whit was on first. I was at short. There was one out. And then it happened, what I had been waiting for all summer—a sharp two-hopper into the glove of the second baseman. As I secured the relay, Whit came in sliding—high—and I was ready to sidearm the ball off his noggin. I don’t know if it was instinct, habit, knowing that beaning him was wrong, or abject fear of reprisal, but in the moment I couldn’t do it. I sidestepped, fired, and jumped, just barely dodging bodily harm myself, as he rolled right at me with considerable malice and well outside the baseline.

I became resigned to my plight, and as summer turned to fall—with Whit still taking the occasional cheap shot at me—I decided that after the season I would quit. I wanted to play my game, but playing here was no longer any fun. Since I wasn’t playing anywhere else—Zeus hadn’t yet recruited me—that was going to be the end of my softball career.

One part of my game at J. J. Walker was a trick play. When a batter lined a base hit to left, I would take a few steps into the outfield to cut off the throw. But instead of tossing the ball to the second baseman, I would wheel and blindly throw to first, hoping to catch the runner off base. If I were to misfire, the nearby fence would prevent the runner from advancing. Runners often fell for this ruse—even after having seen me try it earlier in the season or, worse, earlier in the game. It seemed they were on such a natural high after getting a hit, rounding first base just like the big leaguers on TV, that their brains momentarily froze.

Near the end of the season, Whit came up to bat and, as usual, drilled a hit to center. I secured the relay, and mechanically turned and gunned to first. Despite the fact that Whit had witnessed this play countless times, he had to reverse course, desperately trying to beat the ball back to first. It was shaping up as a bang-bang play. My blind peg was going to beat him, though it was a little high. Then I noticed that Whit was not the only one caught napping. The first baseman, Snowdon, had struck up a conversation with the first-base coach and was out of position. Whit had decided, perhaps for maximum intimidation, to go in standing up. With no first baseman to stop it, the ball smacked off the back of his hairy neck.

I have a good arm, especially for someone my size, but it is well short of a gun, and my relay was coming from center field. Nonetheless, Whit dropped as if shot. There is a confusion that falls over the field when someone may have been injured. Stop the game or play on? My impulse was to urge Snow to pick up the ball and tag Whit since he had lost contact with the base and the soaking rule had been off the books since the Polk administration. But Whit wasn’t getting up, and players on both teams started to check on him. I was trying to arrange my facial features into an appropriate show of concern, and although I was biting my lip, it was all I could do not to laugh. The big jerk had literally run into the ball. Which hadn’t been thrown that hard. There was no way he could be injured. And he was acting like, what?

I cautiously approached the huddle that had formed around him, fearing that as soon as I got close enough Whit would quit playing possum and charge me. But I could soon see that his babyish performance was no ruse. He lay there for a couple more minutes and then got up slowly, nothing damaged but his pride. He walked off the field, collected his bag, and went home—never to return. I still look for him sometimes, in the Times Metro section.

Today I’m having a little of the feeling that Alexander Cartwright must have had when he drew up the rules in 1845 for the Knickerbockers, the social club that first played baseball as we have come to know it. Of Cartwright’s twenty rules, six of the first seven had nothing to do with the number of outs, the distance between the bases, or fair balls. Instead they dealt with club matters: who was eligible to play, when games would be played, how sides should be chosen. Like me, Cartwright was forced to pay to secure something akin to a permit to play on the Elysian Fields. What’s more, if the modified fast-pitch leagues are like baseball in the 1870s, our slow-pitch pickup game is like Cartwright’s antebellum ball, with the pitcher acting as something like a “feeder,” not trying to retire batters but just laying the ball in there to be hit. I want to make the game friendlier and more welcoming. Unlike in the leagues, the pickup-game players vary greatly in ability and demographics. Grade school kids sometimes play along with novice women and sexagenarians. If everyone tries his or her best, that’s all anyone can ask for. But I want the game to be competitive too, an even distribution of experience and ability. Most of all, I don’t want arguing—or rough play.

The bright sun is sending the temperature toward sixty degrees, and, with the shortage of pickup softball opportunities in New York, players are materializing, marching across the FDR Drive as if it were the cornfield in Field of Dreams. More than twenty people appear, many of them new to me, and most pay the thirty-dollar “regular” fee. Regulars, whose numbers are limited to twenty-five, buy a season’s ticket to play, which makes them essentially members of the club. These latter-day Knickerbockers get first dibs on playing over “alternates,” who pay three dollars per game and can play if there are not enough regulars to field two teams. Already I have defrayed half my down payment.

After a brief batting practice, we turn to Cartwright’s practice of captains choosing sides. I pick teams against Weasel, one of the new players. An aspiring actor with a goatee, Weasel is short but with an outsize desire to win. He runs a team in the East Village Softball Association and brought some of his players here today. Weasel sees the world as a Manichean struggle between his team, Josie’s, and d.b.a., the champion team that I played for last year. I call him Weasel because that is what my d.b.a. teammates call him. Today he proposes to convert the game into a surrogate Josie’s/d.b.a. contest. He wants to claim all the guys on Josie’s for his side, giving me, the evil d.b.a. proxy, some of the more talented Saturday regulars. And from there we will pick the rest. Weasel’s modification is OK with me. I want to move things along, the games are supposed to be fair matches, which is what Cartwright specified, and Weasel’s way of choosing teams does produce even sides. We have a spirited, close, and cleanly contested game. Being responsible for the game for the first time, I don’t mind very much when my team loses, though Weasel’s postgame celebration, with all the whooping and high-fives, seems excessive. And I am happy that they want to play two, like a host whose guests stay a little longer than absolutely required. OK, maybe I want another chance, too, to kick Weasel’s little weasel ass.

Training for a Marathon

The dog days conclude in a blur of humidity. In the Sunday league, where I’ve been trying to solidify a spot on Billy’s Machine team, we have a split doubleheader to make up for rainouts. We play the fifth-place Skins at two-thirty and then Rif Raf, led by our former teammate Zeus, which is vying with us for second place. When I get to the Heckscher fields, I learn that Mike the shortstop is going to be absent. I worry that he’s quit over last week’s tiff with Dick, but Billy reports that Mike is having a cortisone shot in his shoulder. With Trey still out, I find myself at the top of the infield depth chart. Woody has moved up to third, and Chad is at second. On top of that, Billy has me leading off for the first time since Opening Day last season.

Right before game time the placid sky is hijacked by an intense cloudburst that sends us scurrying for cover to the oak stand behind the backstop. Just as quickly the rain desists, leaving the afternoon brightly sunny and deeply clammy. Concerned about his win-loss record, Billy reverses the usual pitching order and starts himself in the Skins game, leaving the more difficult Rif Raf for Dick. Billy also may want to take advantage of our pattern of scoring a lot in the first game and not much in the second. As leadoff man I single. I don’t score, but we gradually build a lead. The Skins have holes at the bottom of their order, and Billy is blowing them away with his serviceable heater. Our makeshift infield is making all the plays, with Keith hoovering the occasional low relay. We cruise to an 8–1 win.

A win against Rif Raf in the nightcap would clinch us second place, which is mainly an issue of bragging rights. No matter what, we will face each other in round one of the playoffs. Still, this is not an unimportant game, and I am playing shortstop in it. Billy has, however, moved me back down in the batting order, to seven, my stay at the top as evanescent as the afternoon’s downpour. Clooney, the emergency MD and left fielder, has been hot and is now slotted at leadoff. Dog, the substitute hurler for my Pamela’s team, is pitching for them against Dick. If Dick is sorry for his outburst last week, he isn’t saying. When they come up in the first, Billy is shouting from the bench, “pull hitter,” and waving the outfield around to the left. I shade toward Woody at third. The batter drills Dick’s heater, and I dive to my left and snag it at dirt level. Dick pumps his fist and says, “Big play!” In May or June I would have been on cloud nine with such praise. Now I ignore him, as I throw the ball around my infield and think, “Just pitch the ball, son.”

Our bleachers start to fill up. There are several attractive women, in obvious need of softball guidance, but Chad is unaccountably ignoring them. And for the first time this season I espy the Machine’s number-one fans. Last season, a Hasidic family followed the team. I thought at first that they were Dick’s family, as they were such vocal supporters of him, though it seemed odd as his personal manner is so profane. But it turns out the family just happened into the park one day and became attached to the team and its most annoying player. Billy doesn’t even know their names. Our fan club includes the mother; a girl, the eldest, dressed in a long drab jumper; and two boys, each with earlocks, button-down shirts, dark trousers, and yarmulkes. I find it surprising that we have such fans. In each of my New York marathons, the Williamsburg streets were lined with Hasidim, but they just stared uncomprehendingly, the route becoming eerily silent.

I showed the kid how to throw overhand. | |

The kid’s hero is as usual pitching in and out of trouble. Twice we convert Dick’s walks into double plays. Then we turn the power on, and he has another win. Dick calls his wife on his cell phone and tells her he’s gone ten and oh for the season. He doesn’t mention that pitching wins and losses are highly situational stats, that he has benefited from a ton of run support, and that Billy has given up fewer runs. Still, it’s an impressive record for a pitcher almost voted off the team who can’t throw the ball overhand across the infield. He has won a kind of redemption.

It reminds me of my own. I began this season as the team’s second-string right fielder, batting last. I started out two for thirteen at the plate and seemed on my way to being barked off the team, but I worked my way back with my glove and gradually picked it up at the plate. I am ending the season batting .333, with my OBP up to .400—not great, but not bad either. And Billy has gained enough confidence in me to play me at shortstop and even, once, to let me lead off. This isn’t how it’s going to be when the playoffs begin, when all the guys will be here and Billy will place his best team on the field. But I’ve played well enough to be in the lineup somewhere. Also, I am no longer being yipped at, and only Tommy still calls me Poolie, and then only rarely. More and more I’m hearing “Steady Eddy.”

Somewhere in Ken Burns’s Baseball, a talking head doubtless declares that the baseball season is like a marathon. This is one of those grand analogies that glom themselves onto no sports other than baseball—it is also alleged to be like life, to be emblematic of the struggles of youth, to recapitulate primordial desires to return home, and blah blah. Once pronounced, these supposed truisms are repeated endlessly, as if in an echo chamber. But they wither under the slightest scrutiny, suggesting only that the opportunity to pontificate on baseball is like a drug that inhibits the firing of neurons in a middle-aged man’s critical synapses. Take the biggest cliché of them all. I have news for Mario Cuomo, and when the time comes, he can pass it on to Bart Giamatti. Baseball has nothing to do with wanting to go home. Arguing that it does is the analytical equivalent of trying to yank a curve in the dirt for a tape-measure home run. Baseball is about scoring runs and stopping opponents from scoring runs. Going home is what happens when the game is over. Even in terms of figures of speech, this formulation has it backward. Being sent home is what players are trying their utmost to avoid.

I have played ball and run marathons, to return to the point, and the shortest baseball or softball season lasts at least a few months, while none of marathons I ran took much longer than a few hours. This summer I’ve been on Heckscher #1 in the nightcap of a Sunday softball doubleheader when, with the same amount of time having ticked off on a marathon clock, I would already have my shiny Mylar wrap cinched around me, a one-size-fits-all also-rans medal dangling from my neck, and be padding my way gingerly to the Seventy-Second Street C station. What’s more, the pokiest runner in a marathon will elicit the cheers of tens of thousands of strangers, whereas even professional-quality softball players draw a sleepy audience numbering in the tens, consisting of teammates, opponents, an occasional friend or relative, and a smattering of curiosity seekers whose numbers depend chiefly on the strength of the almighty euro.

If the would-be baseball sages would play within themselves once the cameras are on, they might realize that they’ve stumbled close to a decent analogy. The baseball season—or the softball season, for someone playing in several leagues—is like training for a marathon. Preparing for the twenty-six-mile race means starting months in advance. Although there is no set schedule as there is in baseball or softball, marathoners have to run five or six days a week whether they feel like it or not, and longer on weekends. Late-season marathoners will do the bulk of their training in the summer, it will end in the fall, as does the softball or baseball season, and the weather will often dictate whether and when it is possible to get the activity in. During training, as in the dog days of the softball season, most outings will be hot, often they will be boring, and progress will be incremental. Injury is always a threat. It is possible to get over the psychological humps in both by thinking about a big day in the fall, one that will not go well if too many of the smaller days in the summer are missed. On race day and the last game of the season no one knows exactly what will happen. But almost everyone will lose, and then they will go home.

Copyright notice: Excerpt from pages 35-40, 138-42 of Professor Baseball: Searching for Redemption and the Perfect Lineup on the Softball Diamonds of Central Park by Edwin Amenta, published by the University of Chicago Press. ©2007 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. This text may be used and shared in accordance with the fair-use provisions of U.S. copyright law, and it may be archived and redistributed in electronic form, provided that this entire notice, including copyright information, is carried and provided that the University of Chicago Press is notified and no fee is charged for access. Archiving, redistribution, or republication of this text on other terms, in any medium, requires the consent of the University of Chicago Press. (Footnotes and other references included in the book may have been removed from this online version of the text.)

Edwin Amenta

Professor Baseball: Searching for Redemption and the Perfect Lineup on the Softball Diamonds of Central Park

©2007, 242 pages, 44 halftones

Cloth $25.00 ISBN: 978-0-226-01666-5 (ISBN-10: 0-226-01666-8)

For information on purchasing the book—from bookstores or here online—please go to the webpage for Professor Baseball.

See also:

- Our catalog of biography titles

- Our catalog of sociology titles

- Other excerpts and online essays from University of Chicago Press titles

- Sign up for e-mail notification of new books in this and other subjects

- Read the Chicago Blog